Loan words: My hirsute youthful self gingerly types an early Wild Watch on a borrowed typewriter in an upstairs room of my host family's house in Zushi, Kanagawa Prefecture.

Wild Watch turns 30 this month

By Mark Brazil | Apr 15, 2012

As April 2nd’s 30th anniversary of my first Wild Watch column in The Japan Times neared, I was in India — teeming Delhi to be precise, with its cacophony of people, honking traffic and barking dogs, though a tailorbird would stop and call outside my window, where a palm squirrel never tired of chattering.In the ragged park near my guesthouse, there was no escape into tranquillity such as I might find in an urban park in Japan, but there were lots more birds, along with red-flowering frangipani and silk cotton trees with their bright-orange trumpet flowers.

My brain seems hardwired to search out pockets of nature even during the few days each year I am forced to spend in a city. Delhi had been but base camp for enjoying wildlife encounters galore throughout March as I explored Gujarat, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Assam in a successful search for Asiatic Lion, Bengal Tiger, Striped Hyena, Indian Wolf, Hoolock Gibbon, One-horned Rhino and a host of other species of mammals, birds and reptiles.

It all began when, as a boy growing up in Worcestershire, a county in rural west-central England, all living things entranced me. Fascinating creatures tempted me out into a wider world and drew me out of my painfully shy shell. Later, age 13 and by then at grammar school (junior high and high school combined), my passion for nature at first made me the laughing stock of my class. Paradoxically, though, as time went on that same pursuit of nature — and of birds in particular — earned me respect as the only class member to have traveled the length and breadth of Britain and to have visited its numerous offshore islands.

In due course after that, with an honors degree in biology and English literature from Keele University, three summers spent doing fieldwork in Iceland, and a doctorate under my belt from Stirling University in Scotland, things should have been rosy had Margaret Thatcher not been stalking the land. With the odds of finding a job at home falling fast, I left Britain in late 1981 en route to an unexpected life that was to combine my passions for biology and writing.

After a spell in Malaysia, early 1982 found me living with wonderful Japanese hosts, the Oba family, in Zushi on the coast of Kanagawa Prefecture. From their home, in what remains an ongoing passion, I began exploring Japan. Though in subsequent years I toyed with moving to Ecuador, nearly took a job in Colorado, lived in New Zealand — and should perhaps have returned to Iceland — Japan kept drawing me back.

One evening at my Oba-family base, on a borrowed typewriter I started bashing out a letter of complaint to the Editor of The Japan Times. Where was their coverage of the environment, of biology, of science, of nature, I demanded to know — but part way through a nagging voice in my head recognized I was missing a beat.

That first draft hit the bin and I instead composed a letter offering to write about those subjects, as the paper was failing to cover them. At that time, actually, I’d only had one short article published in Britain, so I couldn’t even call myself a writer.

That a response came by return was a surprise; that it was positive was a revelation. And so it was that I visited the JT offices in Tokyo to seal a verbal deal with the Managing Editor, Gyo Hani, to write 12 pieces on the nature of Japan under my chosen title of Wild Watch. It seemed their previous nature writer had quit sometime before and they had found no replacement.

There was no contract, just a “gentlemen’s agreement” — but the shocker was that Mr. Hani required each story to be illustrated. I was no artist, and a poorly equipped photographer, but nevertheless I set to, drawing rudimentary sketches for each piece, and sent off the batch of 12.

Meanwhile, I had by then become involved in leading birdwatching tours for a British company, so after submitting those articles I left Japan. Of course I had no way of knowing if, when, or how often my stories might appear — that all depended on the fate of a not-so-popular bridge column the paper’s editors wished to replace.

I returned in June after two months of travel in Europe and America to find no word from the The Japan Times — so I called up. “How was the column?” “Fine.” “Had they printed any?” “Yes.” They certainly weren’t giving anything away, so I persevered. “How many had they run?” “Almost all.” Now feeling insecure and uncertain, given the lack of enthusiasm at the editorial end, I tentatively asked whether they might just possibly consider running some more Wild Watch stories? … The answer came back: “Oh we assumed you would just continue submitting.” So continue I did — and three decades later I’m continuing on !

I phased out my own sketches, the last of which appeared in 1989, steadily replacing them with photographs I’d taken interspersed with sketches by a budding young artist named Ichiro Kikuta — and later, with ones by the doyen of Japanese nature art, Masayuki Yabuuchi, until his untimely death at age 60 in 2000.

Now, it is to me a matter of utter amazement that 30 years have passed since my first Wild Watch column was published on April 2, 1982 — and that the column has run without interruption ever since. I have been told that mine is the longest-running single-author natural history column in any paper in the world — and that it is now The Japan Times’ longest-running column.

Such distinctions are all well and good, but I don’t write for fame or fortune, rather in the hope that someone somewhere will find pleasure in my words and descriptions of my experiences, and will be inspired to take up, or sustain, the same kind of lifelong learning that an interest in nature offered me.

Unknown to me, those first columns, published during my absence from Japan, carried a logo-like cartoon image of a wiggly worm peering through a telescope. I hated it from the beginning, but to my utter chagrin it lasted the first five years of the column’s life, until March 1987. Fortunately, however, the name Wild Watch that I’d first suggested continues in use to this day — though I should have copyrighted it back in 1982, as the Internet shows it has been much copied since. Only in very recent years has my “mug shot” appeared alongside my byline.

Several things have happened to me in parallel during the life of this column. First and foremost, I have matured from being a novice writer to a widely published author, and in doing so and writing for more than half my life, I have gone from using a manual typewriter through almost every generation of Apple computer since the mid 1980s. Second, I have been fortunate to be able to pursue my interests in wildlife worldwide; and third I became a sufficiently competent photographer to illustrate my articles.

It all began in 1982 as a weekly column, but after five years, and after juggling around frequent extended periods overseas, I reduced that to twice or three times a month. Then, in 2004, Wild Watch became monthly. My column has appeared on almost every day of the week and I have been overseen by more page editors than I can remember — some who would introduce embarrassingly inaccurate “corrections,” and one, in 1987, who was so difficult to communicate with that I almost gave up writing for the newspaper. However, for the last decade or more I have been shepherded through to regular publication by the assiduous and skilful Andrew Kershaw, an unsung editorial hero behind the scenes, who keeps me on track, on subject and on these pages.

Other changes over the years have seen an end to my columns submitted as typed manuscripts (with carbon copies filed at home), and illustrations — whether sketches, prints or slides of birds or animals — sent in weeks in advance. With the advent of e-mail, I needed only to send slides by post; then ultimately scanning and digital photography rendered even that method obsolete, and I now file stories electronically from wherever in the world I happen to be — and more than 200 of them, dating back to 1999, are digitally archived on The Japan Times website (japantimes.co.jp).

From the mid 1980s until 1998, when I returned to Hokkaido to live, I maintained the column from overseas, making only periodic visits to Japan while working in conservation organizations in Britain and in natural history television in New Zealand.

While my initial remit has always remained the same — to cover the breadth of Japan’s natural history from a personal perspective — I have interspersed this with tales from abroad, with columns about and penned in: Alaska, Antarctica, Australia, Brazil, Canada, England, Galapagos, Germany, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Russia (Kamchatka), Mali, Namibia, New Zealand, Norway, Romania, Sri Lanka and the United States, to recall just a few of the likely 750 Wild Watch instalments amounting to perhaps a million words I’ve written to date.

In the early years I wrote about common creatures and also about places to find wildlife in Japan — a subset of columns that led to my first series of books on Japan: “A Birdwatcher’s Guide to the Tokyo Area,” “A Birdwatcher’s Guide to Honshu” and, in 1987, “A Birdwatcher’s Guide to Japan” — all out of print and collectors items now.

I have covered personal wildlife encounters, conservation issues and controversial topics. I have lambasted government departments on their treatment of the environment, and have also highlighted wildlife hunting, wildlife trading, and issues such as whaling. The more controversial the topic, the more responses I have received from readers, and I am always grateful for feedback.

The most common question I am asked by readers, naturalists, friends and clients I am guiding, is always: “Don’t you ever run out of ideas?” The short answer is “No”.

First and foremost, as a biologist I am fascinated by the natural world. Each and every time I make a foray out into the woods, the mountains or to the coast, whether in Japan or overseas, I am entranced by the species I encounter, the patterns I observe in form, color, growth and behavior. I ponder the larger environmental picture into which all those species fit, and I become absorbed in the minutiae of the details of their lives. Every time I venture out, I encounter something new; a new observation triggers a train of thought, and ideas flow.

However, translating those ideas into a readable format, and finding photographs to match them — now that is a challenge, and sometimes a story remains on the back burner until all the pieces fall into place. But I have no shortage of ideas, and would happily return to writing Wild Watch weekly if space permitted.

One of the earliest questions published by the paper was from a regular reader requesting that The Japan Times publish my column in book form, something they have been considering since 1982, but have never seen fit to pursue. Not to be deterred, I have a manuscript nearing completion, illustrations prepared, and with luck I will have it published later this year.

It has always been my hope to write an additional, more brief, weekly or even daily column I imagine titled Creature Feature to bring readers’ attention to goings-on in the natural world — seasonal blooming, key events in the heavens, the arrival and departure of migratory birds, and so forth — but that’s an idea perhaps for the future when digital media is even more ascendant than now.

Wild Watch has been something of a personal diary of my highlights of nature observations around Japan and around the world, but my goal has always been to showcase the wonderful wildlife that Japan has on offer — and my good fortune in witnessing it.

My journeys, and writings, have taken me from nocturnal wanderings along rushing rivers in Honshu to find and watch the endemic Japanese Giant Salamander, the largest of its kind in the world, to the northern hills of Okinawa to seek out endemic frogs, woodpeckers and rails.

I have thrilled at sightings of Green Turtles, Hammerhead Sharks, flying fish, whales, dolphins, porpoises and Northern Fur Seals all seen from Pacific coastal ferries. I have witnessed the behavior of endemic Giant Flying Squirrels, Japanese Serows, and Japanese Macaques in Honshu, of Siberian Flying Squirrels and Brown Bears in Hokkaido, and of ubiquitous Red Foxes, Tanuki and Sika Deer.

I have returned year after year to the winter haunts of Red-crowned Cranes and Steller’s Sea Eagles in Hokkaido, and never tire of watching them over and over again. I have walked in mangrove forests on Iriomote Island, in ancient cedar forests on Yakushima Island, in broadleaf evergreen forests in Kyushu and Honshu, in northern beech forests in Tohoku and boreal forests in Hokkaido. And no matter how many times before I may have seen it, I ??????am invariably captivated by the flowering of magnolias, mountain cherries and myriad mountain flowers changing week by week through the seasons.

Regular and repeated adventures abroad allow me to witness wildlife spectacles from the Arctic to Antarctica and in the Tropics in between. Fixtures in my annual calendar include wildlife tours of Brazil, Japan and India — worlds apart in culture, history and wildlife, but all spectacular. Yet wherever I travel, I am happy when I return to Hokkaido, and increasingly my work with Japan Nature Guides sees me focusing more on the local opportunities here in this fascinating archipelago.

Meanwhile, from being the fledgling essayist of those first Wild Watch articles in 1982, I have been drawn further and further into the world of writing, penning chapters for travel guides, pieces for in-house hotel magazines, numerous feature articles for broad circulation magazines such as BBC Wildlife and, most recently, writing an app about the mammals of Japan.

But writing has, so far, been a hobby, a sideline, while I have held other jobs in conservation, research, television, or as a university professor. Short-term writing — newspaper and magazine articles — brings rapid gratification. Dream up an idea, pen 1,000 words or so, send them off with a few pictures and, if accepted, payment follows sufficiently quickly to settle some bills.

In the early days of this column, though, even payment was an adventure. Back then, a check would arrive by post from the newspaper in Tokyo, and I would submit it to my bank in Hokkaido. They would then send it back to Tokyo for verification, from where it returned to Hokkaido once more by snail mail. The whole rigmarole could see a full month between my initial receipt of the cheque and my account being credited. Today, credits appear unannounced directly in my bank account. Where is the adventure in that !

Books are a different matter altogether from articles, though I have been drawn to them too. Their research can take years, decades even; their gestation makes that of a human child seem positively rapid, and their writing may take years of “free time.”

My advice to budding authors who ask is, “Don’t do it !” Not unless you are driven, possessed, obsessed or simply have nothing better to do. Books, at least natural history books, consume years of your life and for little return.

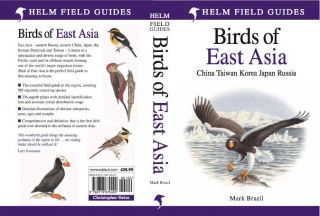

Nonetheless, paralleling Wild Watch, and sometimes inspired by it or by readers of it, I have been obsessed enough to research and write a handful of books, several of them simultaneously. “A Birdwatcher’s Guide to Japan” (1987) was five years in the researching and writing; “The Birds of Japan” (1991) was based on 10 years of preparation and writing; “The Whooper Swan” (2003) was based on more than 20 years’ research and was at least three years in the writing; “A Field Guide to the Birds of East Asia” (2009) was based on nearly 30 years of fieldwork and took five years of writing and editing.

From all this, the direct financial returns are meager, yet the intangible and long-term returns are considerable in terms of circulating my name, making other work possible — and that glow of satisfaction an author gets seeing a copy of their book on sale, thinking: “I produced that.”

My writings have given me sufficient exposure to be of occasional worth to radio and television programmers. They’ve also enabled me to act as a scientific adviser in the making of natural history documentaries around the world and in Japan and — while continuing my current natural history writing commitment for The Japan Times — I have also expanded my exposure as Writer in Residence for JapanVisitor.com, where I concentrate on cultural and natural subjects.

But what of the future? I still have local dreams — to see an Iriomote Cat, a Japanese Badger, an Asiatic Black Bear and a Japanese Dormouse; I still have international dreams — to see African Wild Dogs, Mountain Gorilla, Bonobo and Chimpanzee. And above all I hope to continue to write about what inspires me in the natural world.

Thirty years ago I was shocked at the state of affairs in Japan and wrote in horror about the pace of the spread of concrete, deforestation, losses of coral reefs and of disappearing species.

Those issues remain, but I see hope now. Especially, I see changing attitudes at personal and governmental levels; programmes that have brought back the population of the Red-crowned Crane to more than a 1,000 from near-extinction a century ago; ones that have led to the successful re-establishment of once-extinct wild populations of Oriental Stork and Crested Ibis; and at public perceptions that place increasing value on the rising number of protected Ramsar (wetlands) sites, national parks and UNESCO world natural-heritage sites in this country.

It is no time for complacency; habitat loss continues and shifting climatic patterns exacerbate its impacts, but the Japanese are a resilient and determined people, and once they decide to do something, I know they can achieve it.

There are major challenges ahead, but if the behemoth construction ministry can be convinced to address projects that involve: habitat restoration, returning rivers from concrete canals to their sinuous paths to the sea, and coastlines from mere concrete barrages to their naturally storm-buffering patterns, to burying unsightly wires in beautiful scenic areas, then some of Japan’s classic beauty can be restored.

If the national Forestry Agency and its prefectural counterparts, too, can be convinced to manage natural polycultural forests rather than blanket monocultrual swaths of hay-fever-inducing trees, then both native wildlife and Japan’s human population will live improved lives.

But the magnificent Crested Ibis now flying free again over Sado Island remind me of that Japanese resilience and determination, and give me hope — one of many hopes, and concerns, I hope to be sharing with Wild Watch readers for another 30 years to come.