Iconic mammal of the Arctic, a Musk Ox wanders across the Alaskan tundra © Mark Brazil

Wild Watch Goes to Alaska II

By Mark Brazil | Aug 31, 2017

Alaska! The name alone conjures images of wilderness and “last frontier”, of dramatic landscapes, and fog-shrouded islands. So far though, those adjectives could equally as well describe Hokkaido, the island I call home.

Continuing south through the Bering Sea from the Diomede Islands in the Bering Strait via the Pribilof Islands one eventually reaches the Aleutian Island chain. On some voyages I have been headed westwards at this point, bound for the outer islands of Alaska, Kiska and Attu, then to the Commander Islands of Russia and finally to Kamchatka. On this occasion our ship was eastward bound, eventually towards Seward, but along the way we made first landfall in the Aleutians on Unalaska.

Dutch Harbor, Unalaska Island, is a quaint, colourful Alaskan town famous today for its fisheries. Originally used by the North American Commercial Company to process fur seal pelts, today it is the busiest fishing and processing port in Alaska. Where there are fish there are often birds, and where there are fishing fleets there are often scavengers. It seemed that in Dutch Harbor there were eagles everywhere. The display put on by the dozens of Bald Eagles soaring overhead, flying by, and sitting on buildings, posts and even on the ground, fighting over and feasting on fish was a marvel sufficient to entice even those only mildly interested in birds.

Sailing on eastwards, as we cruised past the five tiny, volcanic Baby Islands we encountered flocks of the diminutive Whiskered Auklet – the holy grail of Bering Sea birding. We were blessed with large numbers of these tiny seabirds in the tidal rip allowing us to watch them in tight groups flying low across the water. Several Humpback Whales put in an appearance too, making this a red-letter day. That was even before we lowered the Zodiacs and set off for an afternoon cruise among the islands admiring seals, sea otters and innumerable seabirds at close range!

Though current sea levels separate Unimak Island from the Alaskan Peninsula proper as the first of the Aleutian archipelago, the island is separated from the Alaskan mainland only by a very narrow channel. As this is the only Aleutian island with a population of bears, it was important to explore ashore in tight groups – there were bear tracks on the beach. Beyond the beach the lush tundra was a marvellous carpet of flowers. Out in the bay there were birds aplenty, most notably Aleutian Terns, a species that breeds as close to Hokkaido as southern Sakhalin yet rarely reaches Japanese waters. Later from the security of the deck of the Silver Discoverer we spotted a female Brown Bear with cubs on the grassy flank of Unimak and through a telescope it was possible to watch as her two spring cubs played and gambolled around their mother on the hillside.

That bear sighting was just the first of many wildlife sightings to follow that day. Soon we were surrounded by Orca, and after that several Humpback Whales provided us with an embarrassment of riches. As the bears receded in scale behind us, numerous Orca and several Humpbacks were in view at the same time ahead of us. This was a real Alaskan experience and one that cannot be repeated elsewhere, not even in Hokkaido.

Sailing up the Pacific coast of the Alaskan Peninsula one passes a cluster of islands known as the Shumagins. The Shumagin Islands are named after one of the sailors on Vitus Bering’s second great Pacific voyage of 1742, who was buried here on their return journey to Russia. Today, Unga Island is perhaps best known amongst expedition travellers as an extraordinary geological site, for here, just by walking the beach, one can admiring a plethora of remnants of an ancient petrified forest. This spectacular coastline is unusual, for the main coastal litter here is not plastic debris, but fossils! The shore is literally littered for several kilometers with scattered fragments of fossilized wood, all of them remnants of an ancient Metasequoia forest, dating back some 70–14 million years – evidence that the region once enjoyed a very much milder climate than it does today.

Fragments of petrified wood were much in evidence, lying along the back of the beach where they had eroded from the low cliff. Further chunks were protruding from the cliff, but the highlights were the standing tree stumps, one of which was still chest high. Overwhelmed in a lahar, a catastrophic volcanic event cascading an avalanche of ash, mud, and rocks, the trees became engulfed in a matrix of mud and angular, unsorted rocks. Rather than decomposing they were leached with silica (derived from the volcanic ash) and petrified into perfectly preserved solid replicas of their once living forms, complete with grain textures and knotholes.

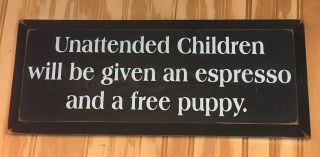

Continuing eastwards along the Alaska Peninsula one eventually reaches the small fishing community of Chignik Bay. Here, in summer, a mosaic of wetland and Sitka Alder forest supports irises, Chocolate Lilies and several species of orchid. There are birds here too, not many, but sightings of Wilson’s Warblers are common. Whereas most of the feeding frenzies I had witnessed in the Bering Sea had involved seabirds here in Chignik Bay those seabird frenzies were easily outdone by the feeding frenzy going on inside the little shop where tra s of delicious, freshly baked doughnuts were being dispensed with at high speed. They were a wonderful rewards for a rainy walks, but best of all was the sign on the wall admonishing parents of small children not to leave them unattended!

For me, the highlight of any visit to the Alaskan coast is to visit wonderful Geographic Harbor. Nearly hidden at the far reaches of Amalik Bay, Geographic Harbor is set in magnificent volcanic scenery, though on my most recent visit it was shrouded in atmospheric mist. We dropped anchor, sent out our scout boats and were soon on the water for a morning’s Zodiac cruise amidst stunning scenery and offshore islands, taking in sightings of Bald Eagle, Marbled Murrelet, Sea Otter, Harbor Porpoise and half-a-dozen or so Brown Bear. The “harbor” here, takes its name from the 1917 National Geographic expedition to explore the area in the aftermath of the famous 1912 Novarupta eruption (the most powerful eruption of the 20th century) in Katmai. As the weather improved, and where the clouds parted, it was possible to see that the mountain cirques above were draped in grey ash and pumice still remaining from the eruption, making the mountains appear as if they were clad in extensive grey snowfields.

Katmai National Park has the world’s largest population of protected Brown Bears, and by small boat it is practical to see several bears in a day and to do so very safely from the water. Exploring by Zodiac is the perfect way of searching for them and it is a rare day in Geographic Harbor when there isn’t at least one bear in view. As they do along Japan’s Shiretoko Peninsula, the bears come down out of the brush to patrol the shoreline, following the receding tide, to search for clams in the sand, or to browse the vegetation at the back of the beach. It is a thrilling prospect to watch a bear, to work out its behavior and position one’s Zodiac such that the animal will, in its own time and at its own undisturbed pace, walk past giving stunning views and photographic opportunities. It is an even more thrilling prospect knowing that there will be multiple opportunities like this to observe bears at close range going about their normal lives each day. How I wish that such opportunities existed along the Shiretoko Peninsula. There, although bear watching boats go out, and although chances are quite good, there is rarely the opportunity to watch at close quarters for the boats are hard-hulled and the captains unlikely ever to go close to shore. The advantage with a rubber Zodiac is that one can nudge along in shallow water almost touching the shore and with every prospect of a completely safe close encounter with a bear. With experience of Polar Bears in Arctic Norway and of Brown Bears in Alaska, I know that the safest way of watching bears is from the water, and the most comfortable way of all is from a Zodiac.

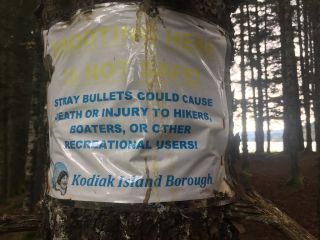

Being around large mammals in the wild is something one must always take seriously, but such mammals have their own agendas and they rarely bother people, in fact they are far more likely to avoid humans than to approach them (Polar Bears are the notable exception for they see everything as possible food!). Being around humans however is far more worrying. Give me wilderness over urban areas any time. My feelings of a strong preference for the security of being around large mammals over that of being around humans was borne out by my final sign sighted on Kodiak Island, Alaska.

Kodiak seems a sleepy town place. This port was initially settled by Russian fur traders in 1784, and established in 1792, by Alexander Baranof, as the first capital of Russia’s North American colonies. Today, Kodiak boasts various attractions such as Erskine House, a National Historic Landmark built in 1809, first used as a fur warehouse and now housing the Kodiak Baranof Museum (dedicated to the man who administered Alaska on behalf of Russia), and also the Alutiiq Museum with its collection of art and cultural objects detailing the lives of the native Aleut, who lived here millennia before the Europeans arrived. There is a Russian Orthodox Church (Holy Resurrection) with prominent blue onion domes dating back to 1794, and a centre for fisheries research with touch tanks of local marine life. There are mysterious moss-draped forests at Fort Abercrombie and rushing streams at the Buskin River, there are wildflowers and wild birds, and in most respects this lovely island is impressive, with one “but” (though it is in fact one mega-but!). Where, except in an active war zone, would you find a sign that warns of the dangers of – stray bullets!!! I feel safer around bears any day, than around humans with guns.

On the final morning of a phenomenal voyage around the Bering Sea and along the coast of Alaska the weather was pleasant, mild and a little misty as we sailed through the spectacular, glaciated, montane scenery surrounding Resurrection Bay bound for Seward. As I stared in awe at that extraordinary scenery I reflected on all that I had experienced in the wilder reaches of Alaska. While my Hokkaido home offers much, it cannot match at all the extent of the wilderness that Alaska offers. Despite that alarming sign about stray bullets I look forward to my next wonderful Wild Alaskan Adventure.

Outro

If you would like to read more about Japan’s natural (and un-natural) history, then you may enjoy Mark’s collection of essays entitled The Nature of Japan: From Dancing Cranes to Flying Fish.

Author, naturalist, lecturer and expedition leader, Dr Mark Brazil has written his Wild Watch column continuously since April 1982, first in The Japan Times for 33 years, and since 2015 here on this website. All Wild Watch articles dating back to 1999 are archived here for your reading pleasure.

Two handy pocket guides The Common and Iconic Birds of Japan and The Common and Iconic Mammals of Japan have also been published and along with The Nature of Japan are available from www.japannatureguides.com.