An endearing young Mountain Gorilla © Mark Brazil

Wild Watch Goes to Africa II Rwanda

By Mark Brazil | Oct 31, 2017

As I set off on my first hike towards the Virunga National Park boundary in Rwanda, the alarming words rattling about in my head were these: “Its the hardest thing I have ever done.”

I have lost count of the number of times I had been told by previous visitors how tough the hike would be, and while some said it would be up to five hours one way, others had given conflicting information saying that it was merely an hour or so. How tough could that be? Most had agreed that though the hike was seriously tough, tougher than anything in their experience, it was well worth it.

The hike sounded so tough that I began to doubt my own physical capability. What if I couldn’t make it? To mitigate that potential embarrassment I increased my daily exercise regime for months in advance (probably not a bad thing anyway), made sure that I walked for more than an hour every day in the months prior to the hike and checked that my boots were comfortably broken in.

The journey began on the day of the Kwita Izina, the 2017 gorilla naming ceremony, with hordes of people streaming towards the gathering ground where the year’s newborn gorillas are named (in their absence of course). As we boarded our vehicle for the short journey to the start of our trek, it was so inspiring to see all those people engaged in a national ceremony focussing on the gorillas. As we checked that we had drinking water, our cameras with spare batteries, our binoculars, and as we listened to our ranger’s briefing about our strategy, our behaviour, and our quarry – the Mountain Gorilla – I was tempted to pinch myself again. Was this really happening, at last? But would I be able to complete the hike?

In a sense the journey had begun in Kigali, when we arrived into Rwanda from Zambia and then begun again when we had commenced our drive through one of the most intensely developed landscapes I have ever seen. As Kigali’s urban sprawl ended, agricultural sprawl began, and it continued, and continued. I’d heard Rwanda (before the 1994 genocide) likened to the Switzerland of Africa. That is not how it struck me in late summer 2017; it seemed more like the market garden of Africa. There were tiny, hand-tilled fields and large plantations of eucalyptus stretching in every direction. At every turn of the road, at every brow of every hill we passed, where I had hoped to see native forest, or at least some kind of natural habitat, I found yet more intensively farmed agricultural land wrapped around and over the landscape blanketing the hills with crops as far as I could see.

In a very different sense though my journey had begun decades before, as a journey of longing. I’d been persuaded eventually (I was reluctant) to take up a place at university and as an undergraduate eventually settled in to read Biology and English Literature, the kind of double honours speciality in which Keele University in England specialised. I’d mistakenly assumed that other students there would be studying subjects in which they too were passionately interested, that others would be crazy keen physicists or chemists or historians or linguists in the same way that I was mad keen about biology. I quickly discovered that the majority of my peers were there marking time, seemingly unsure about why they had chosen one particular academic field over another. They seemed to be merely filling the gap years between school education and a working career; it was a serious let down. At long last though I discovered one brightly burning flame of enthusiasm, another biologist with a natural history bent, who became a pal and ultimately a life-long chum. That intensely channelled enthusiasm for all aspects of the natural world came in the form of Ian Redmond (now Ian Redmond OBE).

This was in the 1970s, when Leakey’s Ladies (Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Biruté Galdikas) were making tremendous strides in primatological research into chimpanzees, gorillas, and orang utan, in Africa and Indonesia. Amazingly, when newly graduated my pal Ian signed up and set off with his degree and his backpack to Rwanda to join the team at Karisoke working with Dian Fossey. Ian’s missives from Rwanda, written in minute script on tissue-paper-thin airmail paper, took weeks to reach me, but told entrancing tales of his life and adventures with gorillas and other wildlife in the forests and mists of the Virungas. This was back in the days, decades before instant access to images, sounds and information from every “remote” part of the world, and long before virtual reality tourism makes visits possible without ever leaving home, when imagination was the fuel of every adventure. I dreamed of visiting Ian in Africa, of sharing in some of those wilderness experiences with him. Vicariously, I continued to soak up his journey, which continued in typewritten tales from Ian the biologist and naturalist ultimately to Ian the ardent conservationist. His direction in life had changed dramatically in the wake of finding Digit, one of his familiars, slaughtered by poachers. I continue to hope that one day he will write his memoir of Digit.

Meanwhile with Ian in Africa my own journey of studies into avian ecology and behaviour took me on from Keele to Stirling in Scotland and Lake Myvatn in Iceland, thence to Japan. It led to a freelance career in conservation, ornithological research, then natural history television and academia, which took me to New Zealand and ultimately brought me back to Japan. At each step of my journey I dreamed of a side-ways step, of following in Ian’s footsteps, or at least of joining him and sharing in one of his African journeys as he fuelled the fire of gorilla or elephant conservation with his boundless, irrepressible enthusiasm.

My own journey eventually veered full-tilt into international nature tourism, but even so, despite the longing, it was many years before an incredible opportunity arose to travel with Mayumi to Africa on behalf of Africa Easy (http://www.africaeasy.com), and to make that journey to Rwanda’s Parc National des Volcans and to make my own first pilgrimage in search of gorillas.

Alas that long-overdue journey was not in Ian’s company, yet he seemed there at every step of the way as I recalled his tales of his experiences, some of them as dramatic as confronting poachers in the forest and being injured by a spear (How many people can include in their list of life-time injuries: spear wound, or trampled by elephant? Ian can, on both accounts).

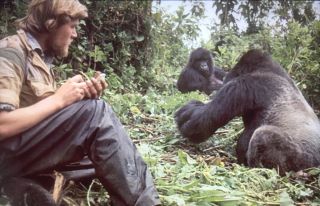

Ian was even more present at the new Dian Fossey Karisoke Visitor Centre. There I was led by the director, Felix Ndagijimana, to a diorama of Dian’s field study desk showing what it had been like back when she had just established her research base in Rwanda in the late 1960s. What should be displayed on that desk but some of Ian’s typescript notes! When I looked around after reading them I noticed a display of images taken by Dian, and there amongst them was one of Ian in his familiar field gear taken sometime in the 1970s sitting beside a family of gorillas. Ian’s many accolades include credits for both David Attenborough’s and Sigourney Weaver’s close encounters with gorillas in front of television and film cameras, and involvement in more than 50 documentaries on gorillas. In a very small way they also include inspiring me, through several decades of my life, to long to visit Rwanda and the mountain gorillas.

Gathering at the park headquarters early one morning in early September, Mayumi, my group, and I were assigned to visit the Isabukuru group. Soon afterwards our hike began. The trail took us between potato and pyrethrum fields as we ascended the volcanic slope towards the park boundary. The park is an island of volcanoes and forest habitat surrounded by a sea of agriculture. The very boundary of the park itself is a dry-stone wall over which porters helped us scramble. Stepping down on the inner side of that wall I felt as if I had passed through the wardrobe from this world into CS Lewis’s magical world of Narnia (read The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe if you haven’t already!) the contrast was so extreme. Suddenly we were in a magical forest with enormously spreading Hagenia trees above us, their thick, wide-spreading branches were draped with epiphytic ferns and mosses, and the ground cover around us included giant dock and giant nettle, semi-familiar species that I knew featured in the gorilla diet.

After a mere two and a half hours of moderate hiking we came into a small clearing and there met the all-important tracking team clad in uniforms bearing the logo of the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International. Responsible for tracking, monitoring and protecting the various groups of mountain gorilla in Rwanda that have been habituated to visitors, it is these folk who put their lives on the line in the battle against poachers. On that particular September day though they led us just a further hundred metres into the forest; then, as we turned yet another corner in the trail, we suddenly realised that we were amongst the Isabukuru family.

A journey and a dream begun forty years earlier suddenly ended and became a reality as we emerged into a clearing occupied by a family in repose. The silverback was a massive and ponderous presence, the nearby females were strong and nurturing, mothers were cradling infants and youngsters were being characteristically boisterous with one of them doing backwards rolls down the slope bumping into others as it went.

Face to face with the Isabukuru family group it was an easy step to realise by just how little DNA we humans differ from our near relatives. The pent-up emotions of the moment were so strong that more than one of band of gorilla trekkers had tears in our eyes.

Had I been able to visit the Virungas back in the 1970s or 1980s I might have spent all day, as Ian had, tracking and following a family in the company of researchers, or removing snares set by poachers, but today gorilla trekking permits last for exactly one hour. Before visiting that seems such an incredibly short time given the lengths to which one must travel to reach their habitat, but in the interests of their safety, their security, and their natural behaviour they receive just one hour-long visit from their human relatives each day. In the company of a gorilla family time warps and an hour flashes by in an instant filled with images of them sitting together, of individuals giving friendly calls, or alarms, or bickering, or munching on vegetation – or breaking wind!

At first there seemed to be a rush, to take in all of the sights, the sounds, and even their distinctive acrid smell. After all this was a dream that had taken decades to translate into reality, but as I always remind my fellow travellers, it is important to put down one’s camera, switch off one’s video and just sit and absorb the experience. Doing that was the ultimate thrill. What an experience!

Walking back through the forest and down the rocky trail between the fields towards our vehicle after that magical hour, I was still euphoric with the experience and reflecting over and over again on the behaviour I had witnessed among both the gorilla family and the human group. When I was training as a biologist it seemed that one of the greatest possible sins we could commit when studying other species was to anthropomorphise about them. Today, as more and more research reveals the great extent of the individual and emotional lives of other species around us, perhaps it is only by anthropomorphising that we can truly understand and value other lives. After all we only diverged from our primate relatives a mere six to ten million years ago and differ from them by less than 2% of our nuclear DNA and only by about 10% of our mitochondrial DNA.

We may never find a way to truly interact with our near relatives; we may never know what they as individuals think or feel, but we can be sure that they do think and feel. We should credit them with those abilities, and acknowledge that allow they do not speak our language, nor we theirs, they are no less worthy of our respect.

And you may be wondering about the severity of the hike. Those words “It’s the hardest thing I have ever done; but it was worth it” had rattled in my mind all morning as we walked until finally I realised their significance. The hike was by no means severe, or even tough, though yes it was uneven, and moderately long, but for anyone unaccustomed to daily physical activity, for anyone who struggles with mobility issues, then it could easily have been the hardest thing they have ever done. There is no doubt though, that it doesn’t matter how many decades you must wait, or how tough the hike is for you, it is absolutely worth it. It was so much worth it that we went again to visit another family the very next day!

Outro

If you would like to read more about Japan’s natural (and un-natural) history, then you may enjoy Mark’s collection of essays entitled The Nature of Japan: From Dancing Cranes to Flying Fish.

Author, naturalist, lecturer and expedition leader, Dr Mark Brazil has written his Wild Watch column continuously since April 1982, first in The Japan Times for 33 years, and since 2015 here on this website. All Wild Watch articles dating back to 1999 are archived here for your reading pleasure.

Two handy pocket guides The Common and Iconic Birds of Japan and The Common and Iconic Mammals of Japan have also been published and along with The Nature of Japan are available from www.japannatureguides.com and next year Mark’s new book, Field Guide to the Birds of Japan, will be published in June.