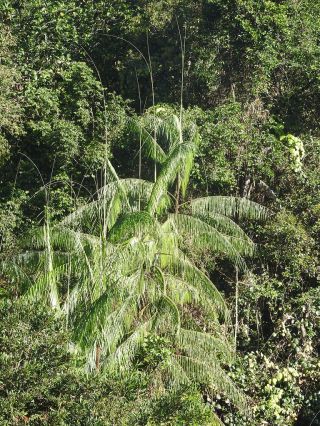

A group of rattans reaching for the light

Rattan: Reaching for the Light

By Mark Brazil | May 10, 2015

Being photophobic is not too bad during the long dark nights of winter, but in summer it is the pits. In my case, it is not so much a response to the light per se, as to shifting light levels that causes my sleep havoc. It is the subtle change from nighttime Stygian blackness to a mere hint of pre-dawn greyness that is sufficient to trigger my wakefulness.

Japan’s painfully early dawns and conversely unfortunately early dusks mean that this is a society that knows nothing of evenings.

Though forced awake by the predawn light and resentful about interrupted slumber, nevertheless I appreciate summer’s brightness for what it provides and symbolizes. Light is Life. It is the quintessential source of our lives, the beneficial energy that powers almost all productivity on Earth.

From my 14th floor aerie I look out across a magnificent swathe of west Hokkaido’s mountainous scenery. It is a rare view, but there are blurs in the foreground. My focus adjusts and as those blurs resolve I realize that I am seeing elements of the Aeolian plankton.

A drift of gossamer silk, carrying a minute spiderling aloft, slinks past on a gentle breeze. The spiderlings that cast themselves off from some lowly spire of vegetation abandoned themselves to the vagaries of the air currents above in much the same way as the medieval Peregrini monks of old who cast themselves off in rudderless boats onto the ocean currents off western Ireland. Each mendicant spiderling and monk accepts a dependency on the unpredictable meanderings of either air or sea.

Feather light seed fluff, like aerial cotton, wafts by in tiny tufts and clumps of airborne generational messengers.

Each tuft, each seed parachute, so light and so far above the ground, unconsciously defies both gravity and time, yet it manages to carry along weighty memories of the endless summers of my distant childhood, the delight of blowing dandelion “clocks” and of watching thistle heads riverside willows send out their feathery cotton clumps carrying their seeds as messengers into the future.

The presence of aerial flotsam distracts me momentarily from the broader vista; I forget my mental ramblings in the mountains beyond and notice instead the quality of the light itself.

The translucence of spring air has given way to a temporary transparency of the atmosphere that is so clear that the air seems like pure water, like polished glass, like highly ranked filtered saké. Distant objects all seem sharp and clear. Recent rains have cleared dust and pollen and spores from the air, leaving only pure and brilliant light.

This 14th floor is at no great height, though it is the highest place for several kilometres in any direction. Yet looking out through crystal clear air I am aware that all of summer’s greenery spreads well below me. The green patina of terrestrial life covers each and every patch of undeveloped ground around here yet nowhere does it exceed even fourth floor window height.

The mightiest tree on Earth, known as Hyperion, the very tallest of all the redwoods Sequoia sempervirensof western North America can only boast a height of 115.7 metres, while Japan’s largest tree the Jomon Sugi a Cryptomeria japonica on the island of Yakushima measures only a fraction of that height at 25.3 metres.

All the green I look out over shares one feature in common, rather than being photophobic like me it is all photosensitive, striving always for the light, grasping at it with an ancestral even primordial longing, yet barely reaching towards the sky.

At ambient temperature all plant life constructs form and structure from light, soil minerals and water. This ancient lesson of photosynthesis learned some two and a half billion years or more ago by the ancestors of cyanobacteria, today allows modern plant species to reach for the light in a myriad miraculous ways.

Converting light energy into structure and growth is something we have yet to truly grasp though inspirational companies such as Goal Zero (www.goalzero.com)and Solar Roadways (www.solarroadways.com)amongst others are paving a path to an exciting future of energy superabundance.

Meanwhile, our earthly plants use blades and stems, trunks and boughs, to reach ever outwards unfurling and spreading their photosynthetic surfaces, grasping at the light and competing for its energy.

Is any land plant group more successful, more seemingly cunning, in this grasping for the light than the tropical rattans? These woody-stemmed climbing palms definitely have ideas above their station. Though trunk-less they nevertheless reach to the same heights as the forest canopy.

While trees take a slow and steady approach inching upwards year-by-year, expanding their girth to support ever-increasing height, the rattans set off in a headlong rush upwards crawling, grasping, and scrambling skyward by clambering on the shoulders of others.

Some 600 species of Rattans, belonging to the Arecales or Palmea palm families are native to the tropics, and though not quite making it into Japan they occur nearby in tropical Southeast Asia along with other Southern Asia, Africa and Australia.

Some rattans produce only single stems, others clusters, while some climb low and others high, but several grow to lengths of 100 metres. Light and durable rattan is also relatively flexible making it suitable for a wide range of crafts from furniture and housing materials to weaving of wicker.

Rapidly renewing itself, rattan harvesting as part of appropriate forest management should function to help protect the tropical rainforests where they grow more rapidly than trees, but alas forests are felled too quickly and rattan resources are declining.

Rattan stems no thicker than my wrist extend many tens of meters up to the forest canopy. Instead of pumping energy into building supportive girth they use that energy for producing climbing equipment.

The slender growing tip of each stem tapers to an apparent point. But brush casually against that tip and one finds that it leaves a painful weal as the rattan’s minute hooked thorns tear at ones flesh.

The outer tapering rattan tip is leafless, extending a few meters beyond the first rattan leaves and all along its length are hooks. Tiny at the tip, larger further back, they are aligned in a spiral around the stem. The questing whip-like tip wavers, is blown about by the breeze and eventually touches something more solid. Growing then in that direction the tip’s hooks allow it to latch onto or among the vegetation up and over which it now grows.

Downward its stem hardens, becoming more wooden, upward that slender tip keeps extending allowing it to climb ever higher.

At mid levels the hooks now swarm in densely packed spiral rows like a monstrous hooked thread on a screw adapted to attaching this plant firmly to the forest around it. At the lowest levels, down near the ground, or even on it, the older stems may snake across the ground, smooth, hook less and leafless - and woody.

Staring up from the floor of a tropical forest into the canopy above the view can hardly be more different from the one from my home.

When in the forest, dense greenery prevails around and above, only dappled light reaches the forest floor and the views are short range.

Any plant aiming to survive needs to garner that light, and scrambling skywards is a race, there are many way to achieve that goal, but the rattan palms certainly have a unique approach.

Outro

Author and naturalist Dr Mark Brazil contributed columns in his Wild Watch series to The Japan Times newspaper for 33 years from April 1982 to March 2015. A collection of Mark’s essays The Nature of Japan has recently been published and is available from www.japannatureguides.com

From April 2015 Wild Watch has moved to a new home on the Japan Nature Guides website. All articles dating back to 1999 are archived here too for your reading pleasure.