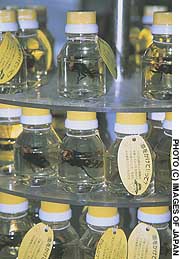

Liquid honey remedies with a hornet in them on sale in Kyushu -- perhaps the only human use for wasps.

Mind over matter and danger signals by design

By Mark Brazil | Sep 19, 2002

Our emotions in relation to other living things are worthy of a whole lifetime of study.I have been with a group of people in a rubber boat within arm’s length of a massive bull Steller’s sea lion armed with vicious canine teeth and repulsive breath; we were armed with cameras. The humans were highly — and mostly pleasurably — excited by their proximity to a large mammal.

I have been in an open Land Rover just meters from a charging African elephant; in a Jeep just a leap away from a tiger; and in an open boat close to orcas, better known as “killer whales.” Yet in each case, my own emotions and those of the people around me were of excitement and a hunger for more.

Conversely, I recall screams from an office that brought me running, only to find someone traumatized by a butterfly that had flown in. Many other times I have been with people who flinched, squealed or ran from a fluttering moth. Spiders? Well, the common reaction to them suggests they must be among the most dangerous creatures on Earth.

Why is it that people are keen to get ever closer to large mammals and birds which, with their beaks, claws, horns or teeth — or by virtue of their huge size — could easily kill or seriously harm them? Yet many of the same folk retreat (at speed) from insects a tiny fraction of their own size?

Of all the insects, I believe spiders and wasps would come out on top as the most feared and hated. Moths, perplexingly, probably come a close third. Whining and whirring insect wings also seem to provoke an almost reflexive flinching and ducking response, while the thrumming beats of a bird’s wing draws admiration. Truly, our range of emotions in response to different creatures is astonishing.

I’d guess that most people find wasps a total turnoff, and can’t wait for that buzzing at the window to end with a terminal thwack of a rolled-up newspaper. These are, though, an astonishing group of creatures, both in their lifestyles and mind-boggling number of kinds. There are chalcid, cuckoo, digger, fairy, fig, gall, jewel, mason, paper, potter, ruby, sand, spider and thread-waisted wasps — and those are not even individual species, but whole groups of species.

Meanwhile, though some wasps live solitary lives; others are social, living in small or large colonies. Some build nests hidden in holes; others conspicuous constructions which hang off rock faces, trees or buildings. Some sip nectar like bees do; others hunt a wide range of prey. I have seen spider wasps stalking spiders and paralyzing them with their stings as a ready meal for their emerging larvae. I have watched monster hornets carving discs of flesh from salmon that have died after spawning. And I have watched tiny fig wasps crawling around their small world in the heart of a fig.

Diverse and fascinating their lifestyles may be, but the idea of wasps being of any benefit to people doesn’t readily spring to mind. However, during one early-summer foray to eastern Kyushu, I developed a sore throat and checked out a roadside stall in search of relief. There, I came across a vendor promoting a most unusual drink. His rows of small bottles were filled with liquid honey — with a large hornet in each. This, he told me, would revive both my spirits and my health. Honey, vinegar, garlic and lemon juice are almost universal in their perceived value as healthy remedies — but quite what advantage I would gain by downing liquid honey laced with a hornet’s body fluids, I never quite fathomed.

Nevertheless, that remains the only commercial use I have known for any member of the wasp family.

What the family is, however, most readily recognized for is its members’ typical black-and-yellow banding. This combination of colors is almost a cliche of nature, implying “venomous and/or dangerous — stay away!”

Nectar-sipping bees are usually aggressive only in defense of their nests, and have barbed stingers. As a consequence, they give their lives in defense, because once they have stung, they cannot withdraw their stinger without tearing themselves apart in the process.

In contrast, wasps are hunters, and they use their stings to kill or paralyze prey. Their stinger, and its associated poison sack, is akin to a minute hypodermic syringe which, as the “needle” is unbarbed, can be used repeatedly to inject poison. Whereas their relatives, the ants, merely spray poison at their enemies, wasps deliver it sharply and precisely.

Although anyone who has been on the receiving end of a wasp’s sting (and knows the burning pain and painful swelling associated with it) will likely be particularly keen to avoid them, even people (and individuals of other species, too) who have never been stung still know to avoid them.

That yellow-and-black banding is the key. Word spreads. We don’t need to be stung to learn that black and yellow spells danger; we learn to fear that combination from our parents and peers. Imagine, though, if every member of the wasp family had adopted a different pattern of coloration . . . red and gold bands, green and white spots, blue and yellow stripes, black and orange blotches, monochromes with dark wings, transparent wings with colorful bodies . . . or black and yellow bands.

With so many different combinations and designs, it would be difficult for birds and mammals to learn which ones were benign and palatable and which were dangerous and/or unpalatable — and so which to avoid, or not. As a consequence, even the venomous species would far more often become victims of predation or destruction — which is not a good Darwinian way to ensure that its genetic heritage moves forward to the next generation.

So, instead of random color combinations among the venomous wasp species, what we find is an astonishing convergence on an almost universal pattern all over the world.

What these insects are doing is mimicking each other.

However, it was another kind of mimicry — of one species of insect by another — that was the first to be discovered — by a 19th-century English naturalist and explorer called Henry Bates. In 1862, he noticed that a number of edible butterflies and moths have evolved colors and patterning that mimics the warning coloration of inedible species and so acts as a protection.

This phenomenon, known as Batesian mimicry, is easy to observe simply by stationing yourself near a large flowering shrub on a sunny day. Such a honey pot will inevitably attract a wide array of visitors, including bees, wasps and other insects. Look out, though, for a little helicopter of an insect, called a hover fly, which resembles a wasp in its coloration but is completely harmless.

In contrast to this kind of mimicry, what the wasp family’s members are doing in evolving their similar banding pattern is known as Millerian mimicry. In this form, distasteful or dangerous insects present potential predators with a single danger signal that is easy to recognize and remember. In consequence, predatory birds or mammals rapidly learn to avoid the entire suite of similarly marked species.

In doing so, of course, they — and we — also give the benefit of the doubt to those species practicing Batesian mimicry.