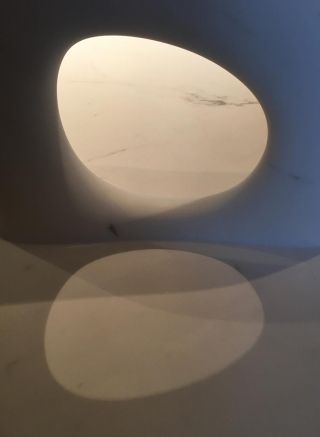

Lake Shikotsu on a calm morning

Kamuy Mintara: Hokkaido, Garden of the Gods

By Mark Brazil | Jul 17, 2015

Summer is a wonderful time to explore Hokkaido; so much to see; so much to learn.

Today, Hokkaido, Japan's northernmost island, seems as modern as the rest of the country, yet despite its population of nearly five million it somehow still retains a little of its Japanese frontier feel.

Delve a little deeper below the recent superficial historical surface and you soon find that Hokkaido has a very different feel, that of the homeland of the Hokkaido Ainu, the indigenous people of northern Japan, southern Sakhalin and the southern Kuril Islands.

The relationship between the Ainu and the Japanese has seen its highs and lows over the last 400 years. At first. to the Japanese the Ainu seemed novel and somewhat alarming northern neighbours, while to the Ainu the Japanese seemed to be suitable partners with whom to trade, much as they did with the peoples to the north and west in Sakhalin and China. Then, as Japanese political fortunes shifted the Ainu fell in their standing and became merely a subjected people blocking the way of the Japanese occupation and development of their Hokkaido homeland.

Overwhelmed and subsumed, families sundered, lands and traditional hunting rights taken, theirs was a history and culture that was doomed to disappear. That disappearance would have been all the more complete because the Ainu language lacks a writing system to help immortalise it. Some had the heart to withstand the sytem imposed upon them; some strove to record, to collect and maintain their traditions, their stories, their arts and music.

Perhaps boosted first by the international recognition they received in 1992 during the UN International Year of Indigenous People, then in 2007 under the Treaty on the rights of Indigenous People, and finally on 6 June 2008 when the Japanese government officially recognized the Ainu as an indigenous population of Japan with their own language, religion and culture, Ainu in Japan and particularly in Hokkaido seem now to be a little more confident, a little more self-assured, that theirs is indeed a living culture.

Ainu is a culture that few outside Japan know of. Even within Japan, few Japanese, even rather few Hokkaido residents seem to acknowledge that they share an island with people who were there before them. Perhaps the recent adoption of "Iramkarapte" the Ainu greeting, as an official welcome to Hokkaido will help bring consciousness of this sharing closer to the surface.

One can only hope that the Japanese government will increasingly recognize that the history of Hokkaido is primarily a history of the Ainu people and that their cultural history, along with its distinctive art, music, wood carving and ceremonial rituals, bring richness, beauty and depth to any visit to this wonderful northern land.

During the late 1990s, I was delighted to be able to work with the BBC and local Ainu communities in Hokkaido in the making of a wildlife documentary entitled Hokkaido: Garden of the Gods.

It was aired first in the UK in April 1999 and then to wide acclaim around the world. Ever since then I have been mulling over how best to introduce visitors more intimately to the wildlife, birdlife, history and culture of Hokkaido and after much planning over the last three years this dream finally came to fruition in the creation of our Kamuy Mintara: Hokkaido, Garden of the Gods tour.

This year's tour was for Expedition Easy, a North American company specialising in exciting travel to unusual places. Our road trip of more than 2,200 km spread over 15 days began and ended again this year at Hokkaido's hub airport at Chitose. Our trip encompassed a broad swathe of western, central, eastern and northeastern Hokkaido on a journey that took is first south of the Daisetsu range, east to Kushiro Marsh, northeast to the Shiretoko Peninsula then back westwards via the mountains to the Ishikari River plain and finally to the volcanoes and lakes of the Shikotsu-Toya national Park.

Our goal was to seek out the summer wildlife of Hokkaido, to watch the resident and summer birds, to see the summer flowers in bloom, to learn about the links between the Ainu of Hokkaido and their pantheon of gods, their Kamuy, and to experience modern Ainu and Japanese culture as we travelled.

We visited no fewer than six national parks, an international Geopark, and various Ramsar sites; we saw collections of Ainu art, witnessed traditional crafts (embroidery and wood carving) being practiced; we listened to modern musical interpretations and watched traditional dance forms; we found wildlife in abundance, and learned, as we went, how so many of the dominant species of Hokkaido were and still are revered by the Ainu.

Through their animistic and pantheistic beliefs Ainu traditionally recognize their dependence on the natural world and their responsibility towards it. They revere animals, birds, rocks, trees, mountains – in fact a myriad things and places.

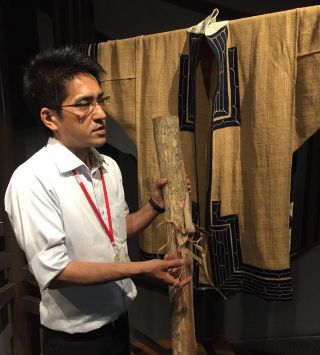

We began our journey at Lake Shikotsu and at a local Ainu cultural centre near Sapporo, known as Pirika Kotan. There we found our first sacred Katsura tree, met our first Kotan Koru Kamuy (in artistic form) and learned that the Ainu made clothing not only out of salmon skin, but also out of tree bark – amongst other things. Lake Shikotsu is ringed with volcanoes, two of them still steaming. The volcanoes of Hokkaido provide another vital element to any journey here – hot springs, and where better to soak away jetlag than in thermally heated water. Hotspring bathing in piping hot water is best experienced out of doors. Baths are segregated, with men and women bathing separately, though don't be surprised young children below school age will go in with whichever parent they prefer.

From Sapporo our journey took us eastwards toward Kushiro with a stop at a Japanese Shinto Shrine along the way so that we could learn a little about Japan's own indigenous religion – Shintoism.

The trees around shrines are typically protected and in these sacred groves many birds and sometimes even animals such as squirrels are to be found. Who knows, but perhaps the roots of the uniquely Japanese Shinto animism may well be in ancestral Ainu beliefs.

Kushiro, the easternmost major city of Hokkaido, not only boasts Japan’s largest peat wetland (a Ramsar site and a national Park), but also an astonishingly attractive city museum with superb displays showcasing the region’s history, culture and natural history, a visit to which set us up for our further explorations of east Hokkaido.

Based in the Kushiro area our goal was to meet the birds known in the Ainu language as Sarurun Kamuy, the God of the Marshes. We know this bird in English as the Red-crowned Crane, and in Japanese it is Tancho. We spent the day in the company of a renowned local photographer and with him we enjoyed encounters not only with cranes, but also with Ural Owls, and a busy colony of Sand Martins. After our first crane sightings we were able to locate them not only in the Kushiro area but in other areas too and on a total of five days out of our trip.

The tawny-orange crane youngsters were being closely tended by their parents. Some were barely a week hold, others that had hatched earlier were closer to two months old, but our very best crane encounter was when we witnessed a pair of bold Red-crowned Crane parents facing off with two female Japanese Deer. The male crane, eager in defence of his young, not only approached the deer with his wings spread to make himself appear large as well as tall, but he almost pecked one on the nose!

It was in the Kushiro area that we also encountered our very first Red Fox – a vixen and her two young cubs outside their den. Playful and delightful these were the first of many, as we tallied an astonishing total of 33 during the course of our two-week tour. Never have I seen so many in summer before, but our timing was fortunate, not only were many young birds fledging, but young mammals were about too.

Travelling northwards next into the region of the Akan NP we encountered our first White-tailed Eagles and on Lake Shirarutoro had a surprise in the shape of a flock of 24 male Falcated Duck – one of Asia’s most attractive waterfowl species.

The slippers of the gods, Eurasian Red Squirrels and Asiatic Chipmunks were much in evidence in the woods of east Hokkaido, but our goal here at Akan was not on land, but in the water. We visited Lake Akan to see one of the extraordinary oddities of Japan, the spherical green algae known first to the Ainu, then to the Japanese, and now too in English as Marimo.

This strange life form, a ball of filamentous algae rolled into its special shape by underwater currents colluding with local topography, exists in very few lakes in the world, most notably in east Hokkaido and northeast Iceland!

On our way we visited the bubbling mud pots and mini steam springs at Bokke, and nearby we bumped into a female Goosander, a large fish-eating duck, with a super brood of 22 young. She was, perhaps, a victim of parasitic crèching (other females mixing their young in with her brood before flying off), the whole gaggle followed her closely like a tiny train with some even riding on her back, much to our amusement.

From the spectacular scenery of the Akan region with its lakes and peaks, we were bound for the equally spectacular Shiretoko Peninsula with its rugged spine and seas to east and west.

We continued our journey via the salmon river and salmon park at Shibetsu, seeing there the enormous Itou and the various other wild salmon that not only serve as food today, but were a vital traditional source of food for the Ainu in centuries past. Fish flesh was not their only valuable product, for the peoples of northeast Asia, the Ainu amongst them, had developed means of curing fish skins and using them to make weather-proof boots and parkas.

The Shiretoko Peninsula, both a national park and a World Heritage Site (registered in 2005) is notorious for brewing its own weather. In fact in winter, the conditions here are so severe that its shores are often invisible beneath a layer of sea-ice at the lowest latitude in the world.

Even in summer the weather along the peninsula is fickle, so it was not too surprising when high waves offshore forced us to cancel one of our boat trips. Nevertheless, we were astonishingly fortunate along the Nemuro Channel and the Sea of Okhotsk shores of this place that the Ainu knew as ‘end of the earth’.

We found yet more foxes – three begging from fishermen as they unloaded their catch, and a fourth carrying a huge fish carcass away along the beach.

We watched tens of thousands of seabirds, mostly long-winged Short-tailed Shearwaters that were bound for the Bering Sea from their Tasmanian or New Zealand breeding grounds, dumpy puffin-like Rhinoceros Auklets that breed in huge numbers in the nearby Kuril Islands, and delightful summer-plumaged Spectacled Guillemots, a localised bird occurring only around the Sea of Okhotsk, in their last stronghold in Japanese waters.

We also encountered two more of our target species: Kimun Kamuy, the God of the Mountains, and Kotan Koru Kamuy, the God of the Village. The former we know as Brown Bear and the latter as Blakiston’s Fish Owl.

Bear-watching in Japan is best done in the Japan Alps (for Asiatic Black Bear), or along the Shiretoko Peninsula for Brown Bear, and what better (and safer) way is there than from a boat. Normally I would consider myself lucky to spot a single bear, or perhaps a single female with a cub or two, but on 27 June the gods of the mountains were smiling on us and we met with female after female, some with tiny cubs-of-the-year born during the winter in their mother’s den, some with larger, one-year-old cubs.

In each case they were foraging along or near the shoreline vacuuming up invertebrates from between the boulders on the beach, scavenging fish remains, and keeping a wary and watchful eye out for each other.

As if bears and fish owls were not enough already, the area offered up yet one more gift before we departed in the shape of Minke Whale.

The skipper of our boat had an uncanny knack for locating these swiftly mobile marine creatures and we were treated to sighting after sighting of no fewer than seven of these sleek animals. A trio of Dall’s Porpoise did not stay around for us to see more than a glimpse, but we saw enough to be reminded that they too live in these waters.

Our side visits to coastal meadows in search of birds found us extensive carpets of gorgeous yellow and orange lilies, wild roses and wild irises in bloom. The palette of colours was delightful.

The next leg of our journey back towards the heart of Hokkaido took us into the Daisetsu Mountains NP. Despite heavy rain, we made our way through the Sounkyo gorge past the Galaxy and Shooting Star waterfalls and eventually up towards the Playground of the Gods – the mountainous hub of this island.

Along our hike we found Kamchatka Fritillaries, which are known to the peoples of North America as Chocolate Lilies. We also found wild orchids, and Middendorff’s Wiegela (a lovely flowering shrub with yellow trumpet-shaped flowers).

The rain may have dampened our trail to the peak of Kurodake, but it did not prevent the birds from singing beautifully. Siberian Rubythroat and Red-flanked Bluetail provided a lovely sounding accompaniment to our wet sloshing!

We continued our travels by way of Abashiri and Bibai, first to try our hand at the traditional mukkuri, the mouth harp or jaw harp, played by the Ainu. Light, portable and easily made from bamboo it proved deceptively simple it was in fact devilishly difficult to extract even a single note from one. We left with further admiration for those who play the mukkuri.

Our journey finally came full circle when we returned to beautiful Lake Shikotsu at the beginning of July.

The beauty of this region belies the fact that it has a violently turbulent volcanic past. In fact the whole island of Hokkaido has had such a turbulent past that it is astonishing that a culture has flourished here despite frequent earthquakes, regular volcanic eruptions, occasional typhoons and infrequent tsunami.

Visiting Hokkaido without understanding the violent forces that have shaped and sundered the landscape, and formed a backdrop to the development of Ainu culture, is to miss the core of the island’s being, so our final visits included one to see Hokkaido’s newest volcanic peak – Showa-shinzan. This raw lava dome, still venting steam, emerged from the landscape between 1943 and 1945 and today is best seen from the flanks of another nearby volcano – Mt Usu in the Shikotsu Toya NP.

This International Geopark, the Toya Caldera and Usu Volcano Geopark, is truly stunning and made a wonderful landscape finale for our trip.

We saved our final cultural finale for Poroto Kotan. Having encountered Ainu arts, crafts, dance and music on our journey around Hokkaido and having studied costume and artefacts in various collections, we were now in a much stronger position to appreciate the construction of the thatched chise (houses), to notice the salmon smoke-drying in the rafters, to notice the sacred inaw offering to the god of the hearth and to appreciate the brief performance of an Iomante ritual.

During our journey we saw more than a hundred species of birds, we encountered wild mammals on an almost daily basis, met photographers, artists, crafts people and fellow travellers and learned that Hokkaido offers innumerable facets. There are its landscapes, wildlife, ten thousand years of human history, surprising open vistas, wild flower meadows, inspiring volcanic peaks and bubbling hot springs, art parks, geo parks and national parks – and much, much more.

Learning about Hokkaido’s many aspects while travelling around its heart is a marvelous way to spend two weeks!

Outro

In 2014 and 2015 Mark has led tours of Hokkaido exploring the theme of Kamuy Mintara: Garden of the Gods. This tour, combining wildlife watching, birdwatching and cultural experiences, will again be offered in 2017 (spring and autumn; final dates to be decided). The maximum group size on each tour will be just five guests; so if you are interested in both the nature and culture of Hokkaido and would like to reserve your place with us, please contact www.expeditioneasy.com

Author and naturalist Dr Mark Brazil contributed columns in his Wild Watch series to The Japan Times newspaper for 33 years from April 1982 to March 2015. A collection of Mark’s essays The Nature of Japan has recently been published and is available from www.japannatureguides.com

In April 2015 Wild Watch moved to a new home on the Japan Nature Guides website. All Wild Watch articles dating back to 1999 are archived here too for your reading pleasure.

Mark lives with his wife Mayumi in western Hokkaido.