Summer sky over Cape Izu, Miyake-jima © Mark Brazil

Isolated in the Izu Islands

By Mark Brazil | Jul 30, 2016

The beautiful subtropical Seven Isles of Izu (Izu Shichito) attract walkers and wanderers, divers, snorkelers, dolphin swimmers, whale watchers and bird watchers, yet they present a strange and fascinating conundrum: Why are they called the seven isles of Izu?

Peruse a map of the ocean south of central Honshu and the conundrum becomes clear. Draw a line stretching from the tip of the Izu Peninsula northeast to the tip of the Boso Peninsula to close off the Sagami Bay and mid-way across your line will bisect Izu Oshima, the largest of the so-called Seven Islands of Izu, with its prominent 764 m peak known as Mt Mihara. Scan down the map several hundred kilometres, or better still sail south past this island, and the blurred lens of the problem becomes a little clearer.

Leaving the large resort island Oshima behind, a string of islands lies ahead (islands named in italics are currently inhabited). First we pass To-shima, then Udone-shima, followed by Nii-jima (with Han-shima and Jinai-to), Shikine-jima, and Kozu-shima; Miyake-jima famous for its camellias, hydrangeas and unique birdlife comes next along with Onohara-jima (actually a cluster of islets), then steep-flanked Mikura-jima with its virgin forest of box trees and chinquapins home to thousands of nesting Streaked Shearwaters, Inamba-jima, and Hachijo-jima. Although Hachijo-jima is the turn around point for the regular Salvia-maru ferry from Tokyo, yet more islands lie beyond it. Next comes Hachijo-kojima, followed by Aogashima, the Bayonnaise Rocks also known as Myojin-sho, then Sumisu-to and Tori-shima world famous as the breeding grounds of the rare Short-tailed Albatross. Finally, some 650 km south of Tokyo, and 76 km beyond Torishima, we reach the basaltic pillar of Sofu-iwa, also known as Lot’s Wife, which rises sheer-sided from the deep ocean.

Now you may see the conundrum – nine of the Seven Isles of Izu are inhabited, and in fact if we add in the list of uninhabited islands we find that the mysterious total of these seven isles is, in reality, at least seventeen!

I have passed those islands by ferry, by expedition cruise ship, and once, and most excitingly, on a small charter vessel bound for distant Torishima. From the low perspective of a small ship these islands are more prominent, and appear more isolated than ever, their shapes etched against sea and sky as if cut like kiri-e from the seascape and the air. Islands glimpsed from a ship impress with their isolation, often with their tropical tranquility (unless a typhoon is brewing), but these islands of Izu create a far stronger and lasting impression, one of turmoil and drama. Their dramatic shapes are those formed by the eructation of lava and ash from the bed of the sea and the belching of noxious fumes and the erosion of wind, waves and rain.

Welcome then to one of the most volcanically active regions of Japan, here volcanoes not only erupt on land, but from the sea too. Here are islands formed by numerous submarine eruptions. For all the apparent drama and violence of their histories, the islands of Izu are in fact but a small part of the Izu-Bonin-Mariana arc. Here incredible forces play out an astonishing transformation as tectonic plates converge along a boundary that extends southwards for more than 2,800 km from Tokyo to beyond Guam, and along which we find the Izu, Bonin and Mariana islands. If we could strip away the waters of the Pacific Ocean and see the ocean bed beneath the waves, we would find it pocked by many more volcanic islands submerged below the current sea level, formed by intense earth-melding forces as the enormous Pacific Plate subducts its way beneath the much smaller Philippine Sea Plate.

Geologists don’t mess about when naming things: they call this narrow strip extending south of Tokyo the “Izu Collision Zone.” This is no car smash or train wreck, or even an imaginary clash of the Titans; we are talking full on collision here between two tectonic plates. Here subduction takes place at a rate of 2-6 cm a year; it is hardly surprising then that the hardy residents of these islands have an unenviable familiarity with earthquakes.

Today, the formidable forces that are continuously striving both to form and tear apart these islands are held in check by a very tenuous cultural leash; they are now bound together, but only lightly, in an administrative entanglement known as the Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park.

First designated in 1936, the national park included only Mt Fuji and Hakone, but it was extended in 1955 to add the Izu Peninsula; then, more recently still, the Izu Islands were added in 1964. The proximity of this 1,227 square kilometre park to the nation’s capital of Tokyo ensures that it is the most visited national park in the country, though admittedly most of these visits are to the Mt Fuji area. Nevertheless, the park is essentially a monument to the earth’s natural forces and the turbulent geological history of the islands that we now call Japan.

Stretching from sublimely iconic Mt Fuji in the north to lush green Hachijojima in the south, and incorporating lakes, calderas, lava flows, gaseous vents and submarine volcanoes, this extensive and disjunct national park is a paradise for those with an interest in geology, especially vulcanology. The Izu Islands themselves represent a group of emergent submarine volcanoes the oldest of which erupted about two million years ago.

My first visit to the Izu Islands was to Miyake-jima in 1982. As an excited and impressionable young naturalist, I was intrigued by this unusual island, by its unique natural history, and by its beautiful scenery. I was keen to seek out the endemic birdlife that had evolved here in the splendid isolation of these oceanic islands. I did not know then that I would never see the island in quite the same way ever again.

My first visit to Miyake-jima was just months before the great fissure eruption and lava flows of 1983 that burst from the flanks of the island’s core – Mt Oyama. That was an event that was to devastate large areas of the west and southwest of the island, changing the scenery dramatically, destroying forests, overwhelming villages and schools and wiping out a large and significant body of freshwater at Shinmyo-ike.

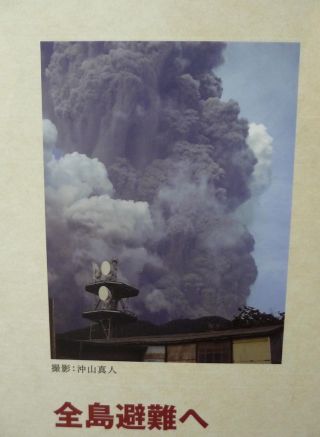

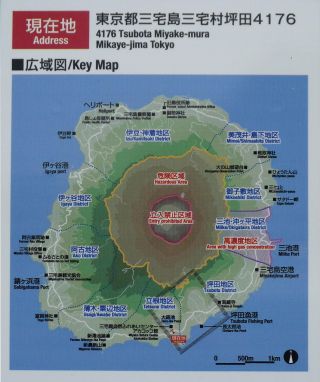

A more recent eruption of Mt Oyama occurred in 2000, this was followed by more than 17,500 earthquakes in just a matter of months and led to the formation of a deep caldera in the mountain’s peak and considerable outpourings of toxic sulphur-dioxide gas. It was that massive gas leak that led to a state of emergency being declared and the forced evacuation of the island until 2005.

Almost unnoticed, given the scale of the geological events unfolding in the archipelago, another event was also set to devastate the ecology of the island, but this was caused deliberately by the introduction of an alien predator – the Japanese Weasel – which went on to dramatically impact the fragile island ecosystem and decimate populations of the island’s endemic birds.

After a series of visits to Miyake-jima through the 1980s and early 1990s there was a long hiatus in the late 1990s and 2000s during which I did not return, but then earlier this decade and again this summer I was able to re-visit, unwittingly part of what some now call gas-mask tourism. On each recent occasion, although I saw no evidence of gas masks, I was astounded by the dramatic changes to the landscape and to the avifauna since my earliest visits, and I noted a stoical approach to life on the islands among the human residents I met there.

In the extraordinarily geologically active Japanese archipelago I suppose we all live with that subliminal sense of imminent potential disruption to our lives and perhaps we all share somewhat in that stoical approach to the events threatening beneath our feet and to the future. Miraculously, from the perspective of my interest in biodiversity, the forests around Tairo-ike have survived the devastation of both of the most recent eruptions and today they harbour the majority of the Izu Islands endemic bird species that draw naturalists from around the world.

Early summer mornings at Tairo-ike are best, before the heat builds and before the cicadas become noisy, the lush evergreen broadleaf forest surrounding the lake is alive with bird song. Here one can hear a wonderful dawn chorus of a unique suite of birds found only in these islands. Long isolated on these islands they have evolved into locally distinct subspecies and species, the very stuff of biological taxonomy.

A constant series of high-pitched notes is the somewhat monotonous sylvan song of a small migratory insect-eating warbler known as Ijima’s Leaf Warbler. These flit very actively like forest nymphs through the trees just beneath the canopy rarely holding still to offer a definitive look, let alone a chance to photograph them.

The endemic, chestnut-cheeked and chestnut-bellied Owston’s Tits are residents here and are far more sluggish; they feed frequently on the acorns of the island’s evergreen oaks and take their time to hammer these seeds open, often perching on a branch and holding the seed between their feet as they do so. Their harsh wheezing dzu-dzu-pee calls draw attention to them as they move slowly through the dark forest. The Izu Island Thrush, rich in black, brown and chestnut is a gorgeous creature that is unfortunately not as common as it once was (before the introduction of those weasels). The thrush forages commonly on the ground, where it sometimes meets another attractive resident in the form of the attractive Japanese Robin.

A bird that does occur elsewhere at several places in Japan, but which is not so easily seen as on Miyake-jima is the Japanese Woodpigeon. Its strange lowing or mooing calls reverberate through the forest, and frequently it can be heard clattering off from a hidden perch or seen sweeping darkly across the forested hillsides flanking the lake. With patience you may find them perching atop dead snags surveying their forest habitat. Several widespread Japanese species also make the islands their home and these include the Japanese Pygmy Woodpecker, which abounds on the island; their brief buzzy calls are commonly heard as they forage along branches and twigs, while the brightly attired Japanese White-eye and Oriental Greenfinch are even more common.

While most of the birds visitors seek out are to be found at Tairo-ike, no birder’s visit to the island is complete without visiting the capes of the west coast, especially Cape Izu with its prominent lighthouse. Here, in the tall grasses that abound just inland from the shore, one can hear the stuttering song of Pleske’s, or Styan’s Grashopper Warbler; await them patiently and they will pop up into view or even make a brief aerial display flight in front of you.

Offshore from the same capes watch seawards in the early mornings and the island will be ringed by hordes of Streaked Shearwaters gliding past just at wave-top height. Larger streamlined shapes flying more directly and higher are Brown Booby, but keep a sharp eye open – you never know what might fly past next on this island famous for its birds.

For those fascinated by the effects of the earth’s forces it is well worth visiting the various geological sites around the island for dramatic and sobering views of the effects of the fissure eruption in 1983 and the gas eruption of 2000. A boardwalk near the coast allows visitors to walk through the ‘field’ of sharp-edged lava beneath which lie destroyed buildings and where one can see the remnants of a school that was overwhelmed by the disaster. Elsewhere a narrow road winds high on to the flank of the island allowing visitors to reach an overlook that affords views seawards to the other islands in the Izu group and landwards to the currently sleeping mountain. Long may it remain dormant!

For anyone visiting Tokyo the Izu islands make for a wonderful getaway from the hustle and bustle of the metropolis.

I’d like to thank Dr Eric Sohn Joo Tan for contributing such wonderful photographs of the birds on Miyake-jima for this article.

Directions to the Izu Islands from Tokyo

By Air from Chofu it takes about 35 min to O-shima Airport, 45 minutes to Miyake-jima and 50 min to Hachijo-jima.

By Ship from Tokyo’s Takeshiba Port by jetfoil it takes 2 hr 20 min to To-shima, 2 h 50 min to Niijima, and 3 h 35 min to Kozushima. From the same port by passenger ferry it takes 5 h 30 min to Miyake-jima 6 hr 30 min to Mikura-jima and 10 hr 20 min to Hachijo-jima. (An English timetable for the various ferries to these and other islands can be found on the www.tokaikisen.co.jp website.

For further details read the Japan Nature Guides web page on birding in the islands.

Outro

If you have read this far, then you may enjoy my previous articles, including recent offerings such as: Japan’s Ubiquitous Scavenger – The Black-eared Kite (June 2016); Oriental Stork Making a Comeback in Japan (May 2016); Daijugarami: Stepping Stone to the Arctic (April 2016); Whale Watching Japan-style: Zamami (March 2016), Snow Monkeys & Cranes of Japan: Spectacular Winter Wildlife (February 2016), Amami Night Safari (January 2016), Life at the Water’s Edge (December 2015), and The Bird that Saved Me from Death (November 2015).

These Wild Watch articles, and many more, can be found on this website, and on our Facebook page (please do visit and hit the “Like” button).

Author, naturalist, lecturer and guide, Dr Mark Brazil has written his Wild Watch column continuously since April 1982. All Wild Watch articles dating back to 1999 are archived here for your reading pleasure.

A collection of Mark’s essays The Nature of Japan and two handy pocket guides The Common and Iconic Birds of Japan and The Common and Iconic Mammals of Japan have been published and are also available from www.japannatureguides.com