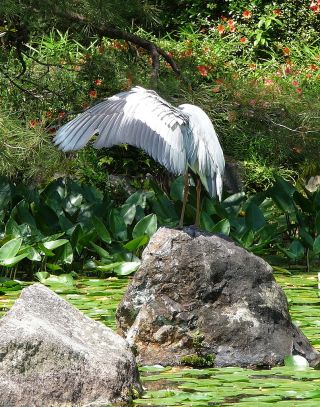

Poised perfection. An adult Grey Heron Ardea cinerea © Mark Brazil

Grey Heron, Master of Japan’s Wetlands

By Mark Brazil | May 30, 2017

Time appears to flow differently for herons; perhaps it even flows around them, leaving them unscathed, as they stand poised and motionless above their reflections. Standing motionless is something to which their minds and muscles are finely attuned. Theirs is a waiting game and they are exceptionally good at it. After what seems an eternity of lingering, they lean forward in ultra slow motion and reach out, pausing again; then there is the very briefest of moments when all of that pent up time and energy seems to pour through them in a barely visible blur as they strike.

As I watch a Grey Heron fishing I note when its leaning ends. The heron’s neck now extends in one apparently effortless stream of concentrated time and motion; its muscles seem at once as fluid as the water below and yet as taught as a drawn crossbow’s string. In the water beneath the heron’s reflection, a dark, unsuspecting shape lazily flicks its tail and inadvertently slips into the danger zone. Like a chameleon about to lash out with its tongue at an insect, the heron carefully gauges the distance to its piscine prey.

Only once the fish has swum into the death-zone will the harnser strike. Like a well-primed spear thrower, the heron straightens its neck and launches the spear blade, its bill, at its reflection. Somewhere below the surface an unsuspecting fish has risked its life by rising towards the surface. The heron’s ‘blade’ seems to ricochet off its mirror image and, in a tightly wound moment of speeded up heron-time a silver-skinned fish is caught. If the heron has judged the distance, the wind, the distorting effect of the water-air interface, and the direction and reaction speed of its prey all to perfection, then, in a blur too fast for the human eye to perceive, it will seem to be instantaneously holding fresh prey between the tips of its mandibles. Ripples spread on the water’s surface; water drips from the bird’s beak; the fish’s tail flicks and stutters; with a flick and a gulp the fish is gone.

On many occasions one or more factors conspire against the heron, not least its prey’s own ultra high-speed response. Fish and frogs have escape reactions driven by their own genetic imperative for survival. On such occasions, when escape velocity exceeds attack speed, and when the adrenalin rush sends prey away from, not towards, the predator, then the morsel of food escapes the death-zone to live another day and the heron’s attempt ends with an embarrassingly empty splash.

Time slows again as the successful hunter pauses; the heron bunches its muscles again, but this time it braces those that power its wings. It crouches; then launches itself into a take off, sinuous neck retracted, long legs extended. The heron’s broad wings appear pale battleship grey and black as it beats into the air. Like a young child’s artistic attempt at sketching ‘seagulls’ against a pastel sky the heron beats slowly on deeply arched, well rounded wings and resembles a huge loose-set M flapping across the picture. Now in slow mode, it cups at the air with its wings, its body rising and falling as it grasps at tenuous aerial support with each beat if its wings. Fully airborne now, its metronomic wing beats are slow and measured giving it the appearance that it is being wafted on a breeze. Long minutes of slow flight away the heron’s nestlings await its return.

Alarmed by a swooping Black-eared Kite the heron gives an expletive ‘fraaaack’ and while still beating its way towards its nesting site it raises its white and black crown feathers into a domed topknot indicative of annoyance and perhaps concern that it might lose its precious nest-bound cargo.

The time that a predator spends between first catching prey and finally consuming it is known to behavioural-ecologists as ‘handling time’, and this time can drive the type and size of prey a predator, such as a heron, pursues. After all, there is no point in capturing prey so large that subduing it takes more energy than the reward contains. Small prey might seem a better choice, as the handling time will be short, but then more time and energy may be consumed in capturing sufficient prey than will be acquired from the prey. Judging the appropriate, optimal, meal size, neither too large nor yet too small, is just one of the many things a predator, such as a Grey Heron must be able to process.

The worldwide heron family, the Ardeidae, is comprised of more than sixty species of bittern, egret, and heron, many of which are colonial. The common large heron of Japan, the Grey Heron Ardea cinerea or Ao-sagi, is one of these. This long-legged wader is an active predator inhabiting all kinds of wetland habitats from freshwater to saltwater including rivers, marshes, ponds, rice fields, lakes, estuaries, mudflats, and even rocky coasts ranging across Eurasia from Western Europe to East Asia and south to southern Africa, South and Southeast Asia.

Once only an uncommon visitor to Hokkaido the Grey Heron can now be found breeding across the prefecture, with birds even remaining to winter in some areas. Here in northern Japan the breeding season begins rather late in the spring, but at the opposite end of Japan, in south-western Kyushu, I have watched them refurbishing their nests in a broad-leaved evergreen wood as early as in February, well before winter had ended. Birds displaying there were already resplendent in breeding plumage, with deeply pink-flushed legs and beaks, and deep blue bare facial skin, many weeks before our northern birds were even considering breeding.

On a much more recent yet cold and misty early summer’s morning near the Ebetsu heronry in west Hokkaido, I watched as these thunder-cloud-grey birds commuted back and forth between their treetop colony and the Ishikari River plain in the distance. From my watch point, I counted more than forty nests, and no doubt more were already obscured in the increasingly dense deciduous foliage of summer. More than thirty birds were in view, some standing at rest, others in the air returning ‘home’ or setting out once more to forage.

The weeks of May and early June are a busy time at Hokkaido heronries. The surviving young herons are growing quickly now and the demands on their parents become ever greater. One adult, standing nearly a metre tall, had perched high in an oak; its bill was drooping amongst its long loose chest plumes, its eyes were closed and I imagined it enjoying a brief period of rest between yet more foraging trips. It seemed all sleeked elegance with its twin black crests either side of its white crown being ruffled by the breeze, but I couldn’t help wondering how exhausted it felt.

Grey Herons feed at any time day or night, but as with so many birds they are most active at dawn or dusk. Between their bouts of foraging they may roost alone or communally, by day or by night, but always on a secure perch on a tree, a cliff, or an isolated rock where they feel safe from potential predators. During the breeding season parents are pushed to forage night and day in order to provide their young with sufficient food.

Although the Grey Heron lives on a diet consisting mainly of fish and eels, it will take aquatic insects, crustaceans, molluscs, crabs, amphibians, snakes, small birds, and small mammals, all of which it catches for itself, though it is not above stooping to occasional acts of piracy – robbing other herons of their hard-won food.

Sometimes, even when successful in the first attack, the heron may yet have a battle to subdue its prey. I recall on one occasion seeing a rather overconfident heron that had snagged a very large eel. It had deftly caught the eel by firmly snapping its beak around it behind its head. The heron’s successful poise vanished quickly as the eel wriggled and writhed with considerable strength. In moments the heron found that the rest of the slimy thing was writhing around the outside of its neck threatening it with asphyxiation. Snake-like, the eel, and its plentiful slime, were soon wrapped around the throat of the heron, which was now engaged in a frantic battle for control. It took many minutes for the heron to wrest final control from its prey, save its neck and slowly swallow the eel. The last I recall of that eel, before the heron flew off, was seeing it still writhing – but now deep inside the heron’s throat. The handling time for that meal was overly long and came at considerable risk to the heron. It could easily have been its last.

The Grey Heron’s prey generally consists of common species taken in proportion to their relative abundance, and particularly those species that are of small or medium size and which are easily caught. In spring in Hokkaido Red-bellied Brown Frogs may form an important seasonal food source as they emerge early in the year. After breeding, and particularly after the young have left the nest, Grey Herons in Hokkaido begin to use the now flooded rice-fields of the various river plains where they forage on the tadpoles of the Japanese Tree Frog. Then as the rice fields begin to dry out during August the herons return to foraging at natural wetland habitats. The rapidly cooling weather of autumn encourages most northern birds to migrate as they require areas of water that remain ice free for four or five months during winter. However, whereas in the past many lakes and rivers in Hokkaido froze over, in recent decades they have frozen more rarely than in the past and large numbers of Grey Herons can even be found here during winter now. The Grey Herons occurring further south in Japan are more sedentary, with their numbers being swollen in winter by arrivals from further north.

Four large, gangly chicks, now nearly fully, grown appear unkempt and ragged looking. Unlike their parents, they are black-crowned and ragged-plumed with long downy filaments disturbing their yet-to-be sleek outlines. Between feeds they wait, hunched and huddled against the morning chill.

This colony is situated in trees above a narrow crescent of water beside an enormous snow dump. Road-cleared snow that was piled mountain-high here over winter thaws only slowly during spring and is far from gone. Waves of frigid air flow from the slowly melting ice mass chilling the environs of the colony and keeping it cooler than expected on a summer’s day.

The young herons stretch occasionally between periods of vigorous preening. It is as if they are irritated by the filaments of down that still cling to their newly emerging plumage. That down was, until recently, vital for their thermoregulation, now it is ruining a fashionable appearance.

The young birds differ from their parents in having black crowns and two-tone bills. The upper half of the bill is a near-black grey, while the lower half is dull yellow from tip to base. At the dividing line between the dark black-grey of the crown and the white cheeks, and just above the gape line of the bill, is the eye. The young herons have bright yellow irises lending them a seemingly malevolent look as they stare, peer and gawp at the world around their nest platform.

The arrival at a nest, of a parent with its crop laden with fish or frogs, sends the youngsters into frenzy. Their necks writhe, and they spread their wings as they jostle and stumble; each is desperate to be the first to monopolise the food supply.

Grey Herons typically fly with their necks looped and retracted, hunched against their chests, but the incoming parent stretched out its neck like a crane as it approached and before landing it had fluffed out its neck feathers into a thickened ruff, raised its crown feathers into a peak and as it landed at the nest its paired, pencil-thin, black nuchal plumes rose straight up in excitement. The youngsters went into a jostling frenzy, first one then another grasped at its parent’s bill.

Finally, like two pairs of large scissors interlocking, the adult grasped the bill of one chick and passed a bolus of regurgitated fish straight into the gullet of the hungry youngster. Ever more frantic the other youngsters now pressed for their turns. Pausing after the food exchange, the adult sat at the nest rim for a while before launching itself once more into the day’s endless task of finding ever more food for its ravenous young.

The exhausting work of raising a brood is shared. After egg-laying, both male and female take turns to incubate the three to five egg clutch for about 25 days. Once hatched, the young will take another seven or eight weeks before they fledge, so from beginning to end the parents are committing to nearly three months of hard work taking turns to feed the young. The soon to fledge birds I watched stretching their wing muscles this morning in Ebetsu had probably hatched from eggs laid during late March or in early April.

Some adults returned to the colony carrying sticks, as if still nest building, or perhaps each was offering a gift of additional nesting material for its mate. One took off into a dogfight, chasing another that has strayed too close to its nest. Meanwhile, other herons nearby were squabbling vocally.

What with outbreaks of squabbling amongst adults and begging amongst young birds, heron colonies are rarely quiet. The Grey Heron’s typical call is a loud rasping “fraanck”, but its range of gargling, croaking and almost barking calls provides the ‘musical’ accompaniment to any visit to a heronry.

The four young herons crowded onto one nest platform seemed at constant risk of pushing each other off the ragged podium of twigs and branches that represents their only home. Above, on another platform, a recently fed young heron shuffled and backed up to the edge of its nest. It raised its wings and tail, paused as if awaiting the perfect moment of time then squirtd a jet of thick, white sticky guano away from its own home, but perilously close to that of others below.

Being hit by guano is just one of the hazards of living high in a tree colony. Heavy rain and cold snaps can all the young at risk, while strong winds may shake eggs, young or even nests from the trees, and even if the young survive the perils of their first winter of independence, they can only expect to live for about five years. Today, thankfully they don’t have to contend with the threat of being hunting, as they are a protected species.

Elsewhere in the world, herons may fall to the guns of hunters mistaking them perhaps for other speceis, and in the past, in Europe at least, roasted heron was a dish fit for a feast. No fewer than four hundred were served to guests following the investiture of George Neville as Archbishop of York in 1465. I wonder what they thought of it. I know of only one person who has eaten heron and he described it as horrible!

Outro

If you would like to read more about Japan’s natural (and un-natural) history, then you may enjoy Mark’s most recent book, a collection of essays entitled The Nature of Japan.

Author, naturalist, lecturer and expedition leader, Dr Mark Brazil has written his Wild Watch column continuously since April 1982, first in The Japan Times for 33 years, and since 2015 here on this website. All Wild Watch articles dating back to 1999 are archived here for your reading pleasure.

Two handy pocket guides The Common and Iconic Birds of Japan and The Common and Iconic Mammals of Japan have also been published and along with The Nature of Japan are available from www.japannatureguides.com