Japanese Giant Salamander Andrias japonicus © Mark Brazil

Chasing Mysterious Giants in the Mountains of Honshu

By Mark Brazil | Mar 31, 2017

The heavily overcast sky delivered first a light rain then a wet snow that thickened, whitened and eventually coated trees and grass alike. Mercifully the road did not turn any more treacherous than indicated by its many winding curves, despite the falling snow. The weather was a surprise for the end of March in Hyogo Prefecture, as was my strange sense of recognition. I’d been in this valley before!

As I drove round one tight curve after another I caught glimpses of the boulder-strewn riverbed beside which the road wound. There it was again – that strong sense of déjà vu. I had definitely seen that bend in the river before; that set of rapids; the rush of white water between that narrowing in the rocky river bed; I knew that after the next curve there would be a bridge – and there was. These were strange phantoms of memory, all the more strange because I had believed I was on a mission to somewhere quite new. Focussing more carefully on the snow and the road I swept these hemories (half memories), or perhaps femories (false memories), aside as the late afternoon light was fading more rapidly than anticipated.

The narrowly winding, forest-lined valley of the Ichi-gawa (Ichi River) suddenly broadened into a small farming community with tiny rice fields heavily protected by deer fences. Many of the farmhouses in the village had a silent air of abandonment. A small sign indicated the way to our minshuku and soon we were settling in to one of those very farmhouses near the head of the valley. Smoke rising from the chimney was a hopeful sign. Just outside the minshuku the trickle of water that was a stream was swollen and heavily rippled from the rain and snow; the evening was turning cold as the last of the light faded. Inside, a wood-burning stove brought welcoming, cosy warmth to the main room. It also brought greater understanding to the Honshu concept of central heating – i.e. heat that is greatest at the centre of the room, ringed by isotherms at descending temperatures as one moves away from the stove! It is a far cry from how we heat our homes in Hokkaido.

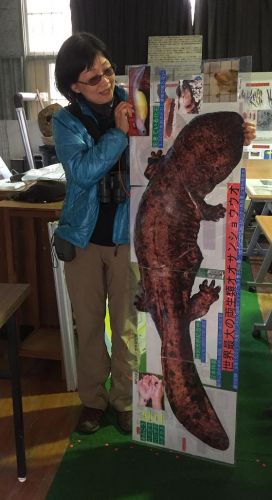

We settled in, made ourselves at home in our museum-like surroundings, and prepared ourselves for the adventure that had brought us to the valley – the presence of a record-breaker. A knock on the door came soon after eight o’clock; friendly faces greeted us and led us out and away from that “central” heating warmth into darkness and damp. From the point of view of the weather, it was a rather grim evening. Our quest in that valley was the Hanzaki, an extraordinary creature that I had only encountered once before one dark night back in September 1993. Outside the region the Hanzaki is better known as Ōsanshōuo (オオサンショウウオ), a name that can be translated literally as “Giant Japanese Pepper Fish”, but we generally know of it as the Japanese Giant Salamander.

We struggled our way along the muddy bank of the small stream by the light of our headlamps, doing what we could not to slip or slide into the water. The gravel-bedded stream over which ripples ran threw back shadows and reflections making scouring the streambed for life difficult. We were searching for a cryptic creature against a dappled background under rippled water – the odds seemed stacked against us.

Giant salamanders, as their name indicates, do indeed grow larger than most of their tribe. In fact, these salamanders grow larger than any other amphibians alive today. Only ancient fossil remains indicate that they are the smaller relatives of even bigger species. I had mentally prepared myself for the fact that in such weather conditions a sighting was unlikely.

The news from our local guides that the usual haunts of the local Hanzaki were unoccupied seemed to reinforce this, but they were hopeful that one creature might be out and about. It felt like we were on the trail of a mythical beast, such as the mischievous imp of Japanese rivers known as Kappa. Some say that the salamander may even be the origin of the ancient Kappa myth.

The water rippling over stones created a blurred mosaic. The streambed was an intricate pattern of shades of beige and brown, from pale sand to almost black in the shadows between the pebbles. It was possible to imagine all sorts of shapes and patterns there, in what seemed like an enormous, endless Rorschach inkblot. I’ve seen creatures in clouds and in the burning embers of a home fire, and could imagine them on that riverbed too. Scanning such a background plays tricks with the eyes. Suddenly, outlined against that mosaic there was a very different shape. Or was it just imagination, a pattern created by ripples? Its colouration was also a range of shades from sandy beige to blackish-brown, but in the light of our lamps I quickly realised that it cast an unmistakeable shadow that revealed an immensely elongated shape. This was no Kappa; this was Hanzaki, a giant salamander no less.

Broadest at the head, with a rounded snout and no discernible eyes, and seemingly neck-less, its body tapered back to a laterally flattened tail. Its stubby limbs were relatively tiny with four digits in front and five stubby toes behind. It was difficult to estimate its size in the poor light and rippled water, but we guessed it was close to a metre in length. It wasn’t a record-breaker by any means, but this individual Old World creature was huge enough to dwarf the largest of the salamanders ever recorded in the New World – the Hellbender of North America.

Japanese Giant Salamanders, known to the scientific community as Andrias japonicus, are completely nocturnal and live in the same kind of cold clear fresh waters that River Otters might occupy in other parts of the world. They grow to much the same size as River Otters, with the largest on record reaching at least 150 cm. They feed on many of the same prey species, such as fish and frogs and so on, but there the resemblance ends, for where the otter is an active pursuit hunter by day and night, chasing down its prey with speed and agility in the water, the giant salamander is a master of the slow life.

Japanese Giant Salamanders are sit-and-wait predators. They are armed only with rows of tiny razor sharp simple teeth, but their jaw is so wide that it seems as if their entire head opens in half. In fact, that is exactly how they hunt. They lie in wait in the cold water for hour after hour, perhaps day after day, waiting for anything that swims or struggles past, whether fish, frog, fallen bird or rodent, or even other smaller salamanders. They don’t need to chase or snap at their prey, all they need to do is sense its near presence, and open up their enormous jaws and the rest comes down to suction. Like a baleen whale gulping in seawater and krill, the salamander engulfs its prey, its sharp teeth ensuring that nothing escapes its grip.

The impassive salamander could easily have been a permanent fixture on the riverbed, but when I returned in the first half-light of the morning it had already gone. It had secreted itself away in a burrow beneath the riverbank where it would wait out the hours of daylight.

Not far away downstream was the home base of a small non-profit research entity and we had made an appointment to visit with its director. En route we explored the valley, pausing to photograph the riverine habitat of the Hanzaki, and at each turn and each stop I became more and more convinced that I had been in this valley long before, perhaps in another life.

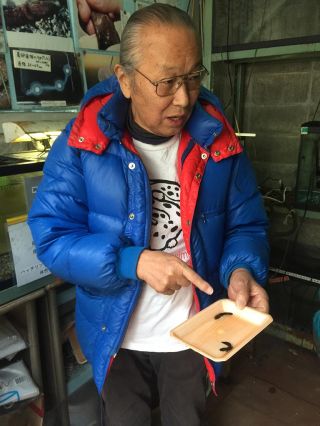

When at last we reached the research facility the face that greeted us was a familiar one – that of the very person who had taken me on my first search for giant salamanders almost twenty-five years earlier the renowned Hanzaki Master Takeyoshi Tochimoto. Over the intervening quarter century each of us had moved, and we had lost touch, I had lost my notes on the locations that I had visited, but he was as indomitable and as passionate about his life’s work with the salamanders as I had remembered.

Over the years since the mid 1970s when he began researching the salamanders one question above all others has dominated his interest – how long do giant salamanders live. After all, it’s the question he is most frequently asked by school children and scholars alike, and no one knows the answer – yet!

To follow their life histories requires individual recognition and that requires marking of some kind. Over the decades of his research Tochimoto has tried tags, branding, rings and photography, but the only guaranteed successes have come with the implanting of transponders.

Of the nearly 1,500 individuals he has identified over the years he is now able to track a number that are more than 20 years old, and some that are even over 30. But these creatures are extremely slow growing, and they don’t grow consistently through life. From hatching they take up to five years just to reach 20 cm, and annually they may only gain 3–5 mm in length a year, but in extremis they may cease growing for years at a time (one of his study animals stopped growing for more than 18 years). Rough calculations suggest that at this rate, the largest animals may live for a hundred years, perhaps even several!

If the transponders last, and future researchers take up Tochimoto’s field work, then perhaps one day we will understand more about their extraordinary longevity. Along the way we may also learn how it is that they can regenerate injured or lost digits and limbs. Think of the potential benefits to medicine of unraveling that biological mystery.

Outro

If you would like to read more about Japan’s natural history and the Japanese Giant Salamander, then you may enjoy Mark’s most recent book, a collection of essays, The Nature of Japan.

Author, naturalist, lecturer and expedition leader, Dr Mark Brazil has written his Wild Watch column continuously since April 1982, first in The Japan Times for 33 years, and since 2015 here on this website. All Wild Watch articles dating back to 1999 are archived here for your reading pleasure.

Two handy pocket guides The Common and Iconic Birds of Japan and The Common and Iconic Mammals of Japan have also been published and along with The Nature of Japan are available from www.japannatureguides.com