Male Autumn Darter Sympetrum frequens, Akiakane © Mark Brazil

Damsels and Dragons: Aerial Dancers

By Mark Brazil | Sep 30, 2016

Although there were only four at first, soon a round dozen devil birds were careering around the summit of Mt Fuppushi. Silently turning, twisting and scything their way through the still air they moved so rapidly that I could barely follow them with my binoculars.

Their top-speed banking turns were so swiftly executed that it seemed as if they disappeared momentarily, as if passing through into another dimension (the one I call the hummingbird dimension), before flashing back into existence, re-materializing many meters away from where I had last seen them and heading in yet another direction.

These Pacific Swifts, airborne black scythes, with snake-tongue tails, are silent, but deadly. They are relatives of the hummingbirds, and their speed is legendary, after all it has been honed over evolutionary time, both by the medium through which they pass and by the behaviour of the prey in pursuit of which they thrash the air and hurtle at breath-taking speed. Their entire life history, since before the first true swifts[1] were written into the ancient fossil record some 50 million years ago, has been driven by one of the dominant life forms on earth – insects. The Pacific Swift is just one more iteration of the arms race between aerial avians and the Class Insecta.

The swifts above me were silent save for just one sound, an occasional paper-rending “phhrrrp” as their narrow, blade-like wings flicker, propelling them in yet another swooping dive in pursuit of Aeolian plankton. It was as if each was an animated microtome, slicing away at the very fabric of their aerial universe one insect at a time.

As I wrote last month, “The hunter and the hunted play out the ancient pattern of life and the nightmare scenario of science fiction thrillers all around us. You just need to know where to look.”

Were these the very last, I wondered. Swifts are typically early migrants and mid September seemed late for them, but then the ocean was only a few minutes wing flickering away (for them) and beyond lay their southbound route for winter warmth in the tropics. Most likely this will be my last sighting of this year.

For an hour they played around the peak, their antics were like those of children at a fair ground – all dash and bravado as if trying to impress with their sliding dives and roller coaster turns. Just once I heard an exuberant scream, as if one of them was remembering springtime passion. Then, in a blink, they were all gone. They vanished out of sight along an invisible broad highway, the aerial flyway used by avian migrants. Fuelled by insects these devil birds had set off in pursuit of warmth and insect-rich lands where they will while away the winter.

It is intriguing to note that the summit cairns and exposed rocks of montane peaks throughout Japan frequently swarm with insects: beetles, bugs, hoverflies, wasps, ladybirds, butterflies, dragonflies and many more. Why they gather there is a mystery to me, but gather they do, and some of them unwittingly fuel the movement of migrant insectivores such as swifts.

It is easy to think of migrants as avian, so visible are they, or perhaps mammalian, if the plains of Africa and wildebeest are familiar to you, yet amazingly insects also experience the wanderlust of seasonal movement. The multi-generational movement of Monarch Butterflies from North America to Central America and back again is a well known, but nonetheless extraordinary migration. What is less well known is that even here in Japan we have migratory insects including both butterflies and dragonflies.

The archipelago of Japan supports more than 200 species of these fascinating ancient insects, and this is their season. The rustling sound of dragonfly swarms hints at the hastening fate of autumn leaves, but unlike the heavy structure of plant leaves their transparent wings appear as delicate as finely blown glass.

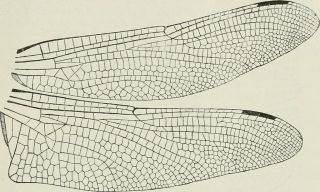

Almost infinitely finer than the finest of stained glass windows, a dragonfly’s wings consists of tiny panels of transparent tissue bounded by fine, strengthening veins, jointed in a net-like pattern. These thinner-than-paper paired wings can propel the “devil’s darning needle” in six directions: forward, backward, up, down, left and right, allowing it to stitch an intricate aerial path through the ether between perch and prey.

Through fine control of their wings dragonflies can switch from hovering to fast forward flight, like a miniature hummingbird, and no doubt aerial drone designers have their sights set on creating some kind of mechanical replica; what a coup that would be, if the dragonflies hadn’t hit upon the design a few hundred million years earlier.

Dragonflies, like the swifts, are hunters of smaller aerialists from midges and mosquitoes to moths, butterflies, damselflies and smaller dragonflies. They hunt on the wing relying on high speed and exceptional eyesight to catch their prey in their feet. Smaller prey may be consumed in flight, while larger prey are subdued first with a bite to the head before being carried to a perch to be consumed.

For all that they are consummate hunters, dragonflies too are hunted. The Northern Hobby, a fast flying falcon, is their nemesis, snatching them in flight, but smaller avian predators, including migratory birds such as Pacific Swifts, are after them too. They must look low as well as high for their predators, for in an unguarded moment, as they dart between the trees or low vegetation, spiders may ensnare them in their webs. Or other insects, such as hornets may chase them down when they are feeling sluggish on cooler days.

The 3,000-5,000 or so species of dragonflies living on Earth today all belong to the order of insects known as Odonata, the toothed ones. They are found almost globally, but are more common in the tropics and subtropics than in the temperate regions, becoming scarce at higher elevations and at high latitudes and absent from the Arctic and Antarctica. So, if you wish to go oding (the term for people who watch dragonflies) in Japan, head for the warmer southern and south-western regions, especially to Shikoku, Kyushu and the Nansei Shoto.

As adults, dragonflies are distinguished by having enormous multifaceted eyes (each of which has over 20,000 ommatidia) filling most of the head, an elongated abdomen, and two uneven pairs of transparent, membranous wings. Not only do their enormous compound eyes occupy most of their head, but more than 80% of their brain is devoted to processing the huge amount of visual information that their eyes gather and deliver during their high speed flight and aerial pursuit of their prey.

A dragonfly’s forewings are narrow while their hind wings are broader and it is this unevenness that allows them to be recognized further as belonging to the suborder Anisoptera (from the Greek meaning uneven wings). Their closest relatives, the damselflies or Zygoptera, are more slender bodied, but are otherwise very similar. There is an easy way to recognize the difference between them though, other than just their size.

The dragonflies typically rest with their wings held open and horizontally, away from the body, like a helicopter with its rotary flight blades at rest, in flight they are fast and agile on strong wings. In contrast, the damselflies have more symmetrical wings, both fore and hind wings being of a similar shape, and as these are hinged they can fold them delicately closed above and along the abdomen; and because of their wing symmetry they have weaker, more fluttery flight than the dragonflies.

Dragonfly flight is almost staggeringly complex as they can generate lift in at least four ways depending on their need. Their wings twist and flex during wingbeats and they are able to adjust the angle, position, speed and length of each stroke, along with the curvature of the wings and the phase of each wing relative to the others. With such astonishingly intimate control they can fly not only in any direction, but in many different ways.

With synchronised-stroking of both hind wings and forewings together they maximise their thrust such as when changing direction rapidly; in phased-stroking the hind wings beat 90° ahead of the forewings allowing them to generate tremendous bursts of speed in pursuit of a territorial intruder or when chasing prey; in counterstroke flight the forewings beat 180° out of phase with the hind wings in such an efficient manner, generating such large amounts of lift, that they can hover and fly at extremely slow speeds without stalling. They can also glide – briefly between bursts of powered flight, in updrafts, such as those over hill tops, or, in the case of females while in tandem when allowing the male to do all the work of flight.

When a Golden-ringed Dragonfly zooms past low and fast nearby it creates quite a stir, its size, proximity and the rustling sound of its wings can easily make one jump. It should, it is not only Japan’s largest dragonfly, but also the largest in the world[2]. Also known as Siebold’s Dragonfly Antogaster sieboldii, in Japanese it is called Oniyanma, and ranges from Hokkaido to the Nansei Shoto. While those in Hokkaido generally reach only 8-9 cm long, elsewhere they measure up to 9-10 cm in length, and have a wingspan of up to 14 cm. That is a greater wingspan than many of our smaller birds, nevertheless the early ancestors of today’s dragonflies, belonging to the order Protodonata, dwarfed the surviving species.

Ancient dragonflies and damselflies reached enormous sizes, as revealed by fossils dating back 325 million years to the Upper Carboniferous period of Europe. One species, Meganeura monyi, had an incredible wingspan of about 68 cm, yet it was dwarfed by the largest known flying insect, a dragonfly known as Meganeuropsis permiana from the early Permian Period some 298 million years or so ago. It had a wingspan of about 75 cm making it larger than a Japanese Sparrowhawk and comparable in wingspan with the Northern Hobby. If one of those ancient dragonflies were to fly past we’d certainly be ducking in alarm. Just how such enormous insects survived is uncertain, but it is speculated that higher oxygen levels and perhaps different air densities allowed them to reach monstrous sizes. Oding back then would have been a hazardous pursuit!

Although we tend to think of dragonflies as extreme aerialists, fast agile fliers snatching their prey in mid air, with some of them capable of migrating across oceans, they actually spend only a matter of days or weeks in that very visible form. For most of their lives they are aquatic, and their aquatic larval stage may last for several years.

Dragonflies have a fascinatingly complex life cycle. Their eggs, laid in clutches of up to 1,500 eggs, take about a week to hatch into tiny aquatic nymphs (also known as naiads) that breathe through abdominal gills. These camouflaged brown, green or grey nymphs are voracious predators eating almost any freshwater invertebrates smaller than themselves. Though their main staple consists of bloodworms and insect larvae, they will even tackle some larger prey such as tadpoles and small fish. Given their voracious appetites and their hardened exoskeletons, in order to grow they must moult multiple times as they mature, with some shedding their skins as many as 15 times as they pass through nymphal stages, or instars, from which, ultimately, the adult dragonfly emerges.

At the very least a draonfly’s larval stage lasts months, while some larger species spend up to five years to complete their life cycle. Ultimately, the naiad ceases feeding, makes its way to the water surface and begins to emerge. First its respiratory system must adjust to breathing air; then eventually it climbs into this new medium up a plant stem where it will moult.

Dragonflies and damselflies, unlike beetles and butterflies, do not pass through an intermediate pupal stage before becoming an adult, and so they are considered to undergo incomplete metamorphosis. The naiad, in its final role, clutches firmly with its claws and anchors itself securely where it will undergo an incredible transformation. The larval chitinous exoskeleton splits behind its head allowing the soft-bodied adult dragonfly to emerge, its body seemingly extending like an old fashioned telescope from its case. The emerging dragonfly’s body expands and eventually hardens, while body fluids are pumped into its wings to expand them to their full extent before they too harden allowing it to wing off into a new existence, trading water for air (and one set of prey and predators for another).

Dragonflies have a complex reproductive strategy too. Many of them, like most birds, are territorial, the adult males vigorously defending territory against their own and other species, protecting: desirable features for foraging, including sunlit stretches of shallow water; crucial features for egg-laying, such as certain plant species or a necessary substrate; and suitable habitat in which larvae may develop.

Mating in dragonflies is also complex. It is a precisely choreographed process, an aerial ballet during which the male must first attract a female in to his territory using his flight and flashy colours, while at the same time jousting with rival males to drive them away. The highly visible external display is matched by well-hidden internal processes, as a male ready to mate must transfer a packet of sperm from his primary genital opening, which is situated near the end of his abdomen, to his secondary genitalia, which lie near the base of his abdomen. Having attracted a mate to his territory, the male then catches the female by the head using the claspers at the very tip of his abdomen allowing him to lead and direct their mating flight and subsequent egg-laying flight. Together they fly in tandem with the male in front. At the time of mating, which may last mere seconds to a minute or two, the female curls her abdomen downwards and forwards under her body to collect the sperm packet from the male’s secondary genitalia completing, as she does so, the distinctive heart or wheel posture.

Continuing in tandem flight, male and female seek out suitable sites at which to deposit eggs. Flying in tandem means that the female uses less energy for flight, as she is partly or wholly supported by her mate, and so she can expend more energy in egg laying. Females of some species use a sharp-edged ovipositor to open a slit in an aquatic plant stem or leaf near the water then thrust their fertilized eggs inside. The females of other species lay their eggs on the surface of vegetation, by shaking them out of her abdomen as she flies along over water, or by tapping the surface of the water repeatedly with her abdomen to shake out her tiny spherical eggs, all so that the cycle of dragonfly life may repeat itself.

Each autumn I find myself feeling sorry for pairs of egg-laying dragonflies seduced by seemingly appropriate wetland sites. I have watched as they dip and tap at the shallow water in a rain soaked metal manhole cover, or in a temporary puddle beside a road. Such sites must seem tempting to them, but very quickly they dry out leaving those eggs desiccated and wasted with no chance of developing.

Dragonfly eggs and larvae are susceptible to drying out, while as adults they are very susceptible to changing temperatures. As they are “cold-blooded” the adults must reach certain temperatures for their flight muscles to be effective, but by basking in the sun they can warm up, and through the day they can change their orientation to the sun in order to thermoregulate, either to warm up further or to avoid overheating. Larger dragonflies, like bumblebees, also use wing-whirring to warm up, this involves rapidly vibrating their wings generating heat in their flight muscles, rather like revving an engine in neutral.

Each autumn swarms of dragonflies abound here in Japan and few are more conspicuous than the Autumn Darter Sympetrum frequens, known as Akiakane in Japanese. This species is endemic to Japan and is unusually migratory – it migrates up and down mountainsides, feeding at higher elevations then returning to the lowlands to breed in wetlands including wet rice fields.

Also abundant is the Red Dragonfly Sympetrum baccha matutinum known here as Konoshimetonbo. They can be found basking in the sun on walls, tree trunks and any exposed perch, keeping warm in the last rays of the season until the first frosts catch them out and finish them off.

In Japan, dragonflies symbolize approaching autumn and are admired and respected so much that they were symbols of courage, strength, happiness, agility, power, and even victory. Dragonflies they have cultural significance in many other areas too from the Americas to ancient Egypt, and from Europe to East Asia.

In Europe they used to be considered sinister creatures belonging to witches or even Satan, sent to Earth to cause chaos and confusion. They were known as Ear Cutter, Devil’s Darning Needle, Adderbolt and Horse Stinger. In some folk tales they were creatures the devil used to weigh people’s souls, in others they were considered eye pokers or eye snatchers. Yet they were also admired for their agile flight, their speed and their bright iridescent colours and were admired by poets and authors alike.

The great writer on matters Japanese, Lafcadio Hearn, noted that dragonfly haiku by Japanese poets were “almost as numerous as are the dragonflies themselves in the early autumn.”

One such famous observer/poet, Matsuo Basho (1644-1694), also observed and described dragonflies in his haiku. In one he wrote:

The dragonfly

can't quite land

on that blade of grass.

In those few words one can easily see his image of a territorial dragonfly repeatedly making passes over a tiny perch. While in another he commented:

Crimson pepper pod

add two pairs of wings, and look

darting dragonfly.

No doubt he was describing one of the innumerable Autumn Darters, or Red Dragonflies that go to make up autumn here in Akitsushima.

One interpretation of this ancient name, Akitsushima, for Japan is “Dragonfly Island”, a name that refers to a legend about Emperor Jinmu in which the mythical founder of Japan was bitten by a mosquito, but was saved from further bites by a dragonfly that ate his tormentor.

In this Land of Dragonflies I hope you enjoy the autumn!

Outro

If you have read this far, then you may enjoy my previous articles, including recent offerings such as: Halcyon Days (August 2016); Isolated in the Izu Islands (July 2016); Japan’s Ubiquitous Scavenger – The Black-eared Kite (June 2016); Oriental Stork Making a Comeback in Japan (May 2016); Daijugarami: Stepping Stone to the Arctic (April 2016); Whale Watching Japan-style: Zamami (March 2016), Snow Monkeys & Cranes of Japan: Spectacular Winter Wildlife (February 2016), and Amami Night Safari (January 2016).

These Wild Watch articles, and many more, can be found on this website, and on our Facebook page (please do visit and hit the “Like” button).

Author, naturalist, lecturer and guide, Dr Mark Brazil has written his Wild Watch column continuously since April 1982, first in The Japan Times for 33 years, and since 2015 here on this website. All Wild Watch articles dating back to 1999 are archived here for your reading pleasure.

A collection of Mark’s essays The Nature of Japan and two handy pocket guides The Common and Iconic Birds of Japan and The Common and Iconic Mammals of Japan have been published and are also available from www.japannatureguides.com

[1] The first fossil true swift that I am aware of is the 49 million year old Scanish Swift, a beautifully preserved fossil of which was found in Germany.

[2] The only odonate to exceed it is a Forest Giant Damselfly Megaloprepus caerulatus of Central and South America, which reaches a length of 12 cm and a has wingspan of up to 19 cm.