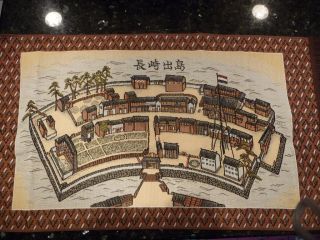

Tapestry depicting Dejima, Nagasaki © Mark Brazil

Kaempfer, Thunberg, Siebold and Blakiston: names in Japanese natural history that live on

By Mark Brazil | May 30, 2018

Wander through the pages of any natural history volume on the plants, birds, mammals or insects of Japan and you will notice that the majority of names, whether English, Japanese or scientific, refer to a species’ unique distinguishing characteristics, perhaps referencing its colour, its morphology, its habitat, or behaviour, or something else about it that is visually striking. In short, we are delving into the realms of taxonomic etymology!

In some cases, seemingly random names appear to have been used; names that appear at first sight to be those of people, and that is what they are. Such species are uniquely eponymous. Some such names are given to honour individuals, eponymously, perhaps referencing a sponsor, a mentor, or a famous figure, such as the gecko Homonota darwinii named after the great British naturalist Charles Darwin, the rare butterfly Euptychia attenboroughi, named in 2017 after Sir David Attenborough, or the particularly golden-haired horsefly recently named after Beyonce, Scaptia beyonceae. The likes of Bob Marley, J. R. R. Tolkien, President Obama, and Frank Zappa (and many more public figures) have all been recognised in this way by taxonomic biologists. Being commemorated in name conveys a kind of inescapable immortality.

Taxonomists are human, and some of the names they have chosen are not so much in honour as in insult of someone with whom they have crossed scientific swords. The father of modern taxonomy, the Swede, Carolus Linnaeus, even stooped to damning unfortunate colleagues with negative names. For example, Linnaeus named a small, unattractive and unpleasantly sticky plant with tiny flowers Siegesbeckia orientalis after Prussian botanist Johann Siegesbeck, because Siegesbeck had criticized Linnaeus’s revolutionary binomial naming system.

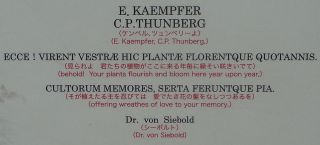

Our human lives are so brief, like candles flickering and guttering in the dark, yet the names of some individuals linger on through their eponyms. Echoes of their lives resonate through the centuries as cultural memes that pass from generation to generation perhaps never to be forgotten. The natural history of Japan is replete with examples, but four names are, for me, outstanding: Kaempfer, Thunberg, Siebold and Blakiston. These four names and their histories span four centuries, but in natural history they are forever, immortal.

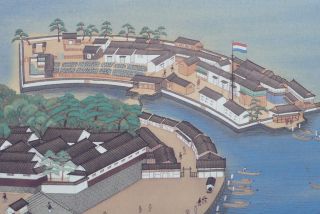

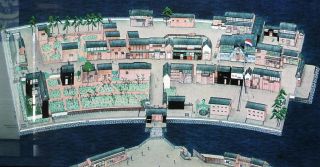

Japan’s centuries of Sakoku, during which the Tokugawa Shogunate, in a strictly isolationist manner, controlled and regulated relations and trade between Japan and other countries meant that, amongst other things, foreigners were barred from entering Japan. This restrictive period, which lasted from the early 1600s to the mid 1850s, meant that opportunities for the exchange of knowledge between Japan and the world were extremely limited. Like a chink in a solid door, the tiny island of Dejima, in Nagasaki, acted as the narrowest of conduits through which knowledge and trade with the west could pass. The permitted, but highly restricted Dutch trading enclave there was confined on a tiny fan-shaped island just 120 m by 75 m. Those who worked there and their overseers nevertheless required their own physician, and the physicians of Dejima proved to be enterprising men who imparted a vast store of knowledge about Japan to the western world and conversely introduced many aspects of western life to Japan – not least amongst them elements of western medicine.

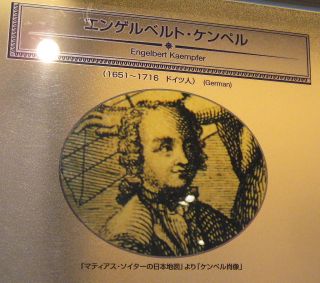

The first who garnered international attention was Engelbert Kaempfer (born 16 September 1651 – died 2 November 1716) a German who had trained as a physician. Like so many physicians and clergymen of past centuries he was also an ardent naturalist and his travels as a physician allowed him to collect specimens of previously undescribed species from poorly known parts of the world, including Japan.

In September 1690, when Kaempfer arrived at Dejima, it was the only Japanese trading port open to westerners. Kaempfer was to remain in Japan for little more than two years, but was permitted on occasions to leave the tiny island of Dejima. It was during one of those brief excursions that he noted and described the, then poorly known and now widely planted, living fossil tree Ginkgo biloba. Among the many species named after him one in particular the Japanese Larch or Karamatsushould be familiar to anyone who has travelled in central or northern Honshu, or to Hokkaido, where it was introduced. This delightfully colourful and deciduous conifer bears the scientific name Larix kaempferiin honour of the first German physician-naturalist of Dejima.

A half century later Dejima was once more home to a foreign naturalist who has left a significant mark. Swedish naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg (born 11 November 1743 – died 8 August 1828) has been honoured as the “Japanese Linnaeus”, so great was his contribution here. A student under Linnaeus at Uppsala University, Thunberg studied medicine and natural philosophy and was then invited to collect botanical specimens from Dutch colonies including the tiny Dutch enclave in Dejima.

First, as a ship’s surgeon, Thunberg devoted himself to learning the Dutch language so that he could pass as a Dutch merchant (as they were the only westerners allowed into Japan at that time). He arrived at Dejima in August 1775 and became its chief surgeon remaining there like Kaempfer for just two years. Trading his knowledge of western medicine for local botanical specimens he began his exploration of Japan’s flora.

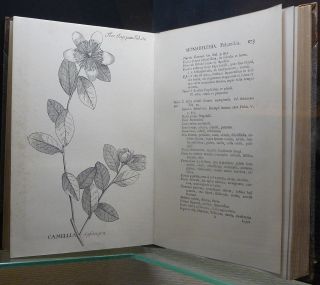

Thunberg was extraordinarily fortunate to have been allowed to travel from Nagasaki to Edo (Tokyo) in 1776, and that journey overland allowed him to collect and preserve numerous plant specimens. His studies and his collections allowed him to undertake the first description of the Japanese flora, which was ultimately published in 1784, after his return to Sweden, as “Flora Japonica”. His meandering return journey from Japan, from where he set out in November 1776, took him three years. On his way back to Sweden he visited London and met with contemporary botanist Sir Joseph Banks, himself commemorated in innumerable plant names, in particular in the generic name Banksiafor the many species commonly known as Australian Honeysuckles. In London, Thunberg was able to examine the collection of his predecessor at Dejima, Engelbert Kaempfer, and we may only imagine how thrilling an experience that must have been for him.

In the measured footsteps of Kaempfer and Thunberg came Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold (born 17 February 1796 – died 18 October 1866), another German physician, who was destined to leave behind an astonishing legacy. Building on the works of his predecessors, Siebold’s contributions to our knowledge of the Japanese flora and fauna were enormous. As with Thunberg, Siebold became a ship’s doctor, learned Dutch and like both Kaempfer and Thunberg before him he was posted to Dejima, arriving there in June 1823.

Trading his scientific and medical knowledge for information on Japan’s customs, culture and natural history, at a time when it seems Japanese were increasingly hungry for such knowledge, Siebold was eventually granted more extended access beyond the close confines of internment on Dejima. Siebold’s life in Dejima included ‘marrying’ and fathering a daughter. He honoured his ‘wife’ by naming a Hydrangea Hydrangea otaksaafter his pet name for her, and honoured his daughter with sufficient training and skills for her to become a highly regarded physician in her own right. Siebold’s own collections rapidly expanded as his grateful patients ‘paid’ him in kind with objects ranging from ethnographic artefacts and artworks to natural history specimens, and as he sent Japanese specimen collectors into the countryside. As was typical in that period, the specimens he collected, including the first specimen of the huge Japanese Giant Salamander (Andrias japonicus), were sent in shipments to various European museums.

Siebold’s enquiring mind and acquisitive collecting eventually landed him in trouble, as during a journey to Edo he was caught with several maps in his possession (a treasonous act at that time). He was first arrested and placed under house arrest; then ultimately in October 1829 his six-year sojourn in Japan came to an end when he was expelled having been accused of spying on behalf of Russia. Settling in Leiden he established a small private museum and wrote a number of books himself on Japanese ethnography, geography and natural history as well as collections of literature and a dictionary.

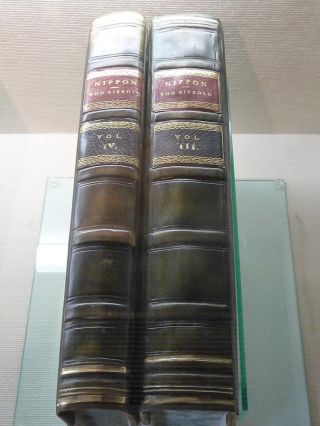

I first came across Siebold’s illustrious name in the context of the famous, multi-volume Fauna Japonica published from 1833-1850, which relied heavily on his specimen collection. It is renowned as having made the Japanese fauna the best-described non-European fauna of the times. Further serving to establish Siebold’s name as one to live forever was his workFlora Japonicaco-authored with German botanist Joseph Gerhard Zuccarini, much of which was actually published posthumously. Siebold’s legacy lives on not only in his published works and the species named after him, but also in the species that he introduced to Europe and which have subsequently spread around the world, which included a range of species from Azaleas and butterburs to the larch tree named after his predecessor Kaempfer. His knowledge of then closed and isolated Japan made him an invaluable expert and adviser, and unsurprisingly even the American Commodore Matthew Perry, renowned for ‘opening’ Japan, is said to have consulted Siebold.

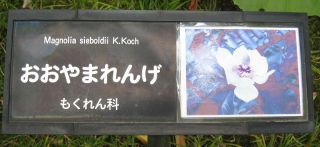

Perhaps little known in Europe or North America today, outside the limited spheres of botany and horticulture, Siebold (Shiborudo) is well known in Japan and amongst naturalists, both as an important historical figure and as someone amply commemorated in species names, from a bird, the White-bellied Green Pigeon Treron sieboldii, to various trees and shrubs including Siebold’s Magnolia Magnolia sieboldii,Siebold’s Viburnum, Southern Japanese Hemlock Tsuga sieboldii, and even a fern, Siebold’s Wood FernDryopteris sieboldii.

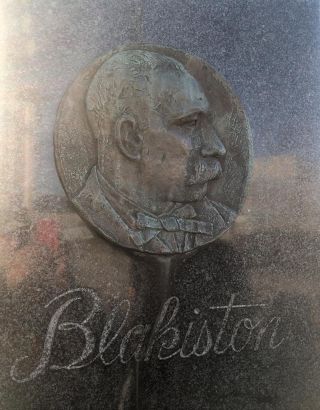

Whereas in earlier centuries the fragment of Nagasaki known as Dejima was the only conduit for knowledge between Japan and the west, during the mid and late 19thcentury, especially with the Meiji restoration, came the relaxation of certain restrictions. A number of other ports were opened to overseas trade, including Kobe, Yokohama and especially Hakodate. It was to Hakodate, which had opened first in 1854, that the British merchant and naturalist Captain Thomas Wright Blakiston (born 27 December 1832 – died 15 October 1891) moved to establish initially a wood milling business.

With far fewer restrictions placed on the movements of foreigners in Japan at that time, Blakiston was able, during his twenty-three year residence in Hakodate from 1861 to 1884, to collect natural history specimens himself and send out collectors to bring back specimens to him. In communication with entomologist Henry Pryer (1850-1888) who lived in Yokohama, Blakiston with Pryer’s help published a Catalogue of the Birds of Japan. That ground breaking ornithological work provided the basis for a later compendious volume Birds of the Japanese Empireby Henry Seebohm.

Blakiston was the first to recognize the fundamental difference between the fauna of Hokkaido, which was more closely related with that of northern Asia, from that of Honshu, which was more closely related to that of southern Asia. The Tsugaru Strait that separates Hokkaido from Honshu has, since Blakiston’s time been recognized as a significant zoogeographical boundary otherwise known now as Blakiston’s Line.

One of the specimens collected by Blakiston and shipped to Britain was of an enormous owl, which now also bears Blakiston’s name. Known as Blakiston’s Fish Owl, Bubo blakistoniit is both rare and endangered, but I have had the good fortune of watching it in the wild in Hokkaido and in visiting the collection of specimens housed in Tring, UK, to see that original specimen taken by Blakiston. The collection at Tring, in the English countryside, began as the private collection of Lord Lionel Walter, Baron Rothschild (1868-1937).

Today, the Tring-based collection houses almost 750,000 specimens of more than 95 per cent of the world’s bird species, among them are 8,000 type specimens (the first and representative specimen collected of a species). The enormous diversity of priceless material there was certainly overwhelming, but in the company of fish owl researcher Mr Yamamoto Sumio, only once specimen captured and held our attention – the very specimen of the owl sent by Blakiston. Having stood together on cold winter nights beside frozen rivers in east Hokkaido watching and listening to this bird, seeing that rare specimen in Tring was as if we had been transported back in time and we could imagine what it must have been like to have been an ornithologist in Japan in the late 1800s.

Numerous Japanese naturalists have each left their mark on the natural history of this country, but few have achieved the great significance and fame accruing to Kaempfer, Thunberg, Siebold and Blakiston, whose pioneering work allowed the west to learn so much about this fascinating country.

Outro

In June 2018, Mark’s latest book, A Field Guide to the Birds of Japan, will be published.

If you would like to read more about Japan’s natural (and un-natural) history, then you may enjoy Mark’s collection of essays entitled The Nature of Japan: From Dancing Cranes to Flying Fish.

Author, naturalist, lecturer and expedition leader, Dr Mark Brazil has written his Wild Watchcolumn continuously since April 1982, first in The Japan Timesfor 33 years, and since 2015 here on this website. All Wild Watch articles dating back to 1999 are archived here for your reading pleasure.

Two handy pocket guides The Common and Iconic Birds of Japanand The Common and Iconic Mammals of Japanhave also been published and along with The Nature of Japanare available from www.japannatureguides.com