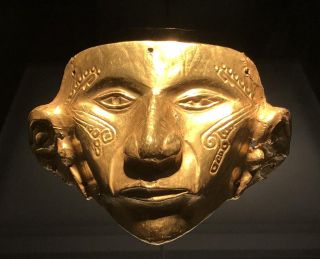

Colombia is rich in ancient gold culture © Mark Brazil

Wild Watch Goes to Colombia

By Mark Brazil | Apr 30, 2018

My first taste of Colombia came most unexpectedly. It was 1980, I was not a coffee drinker and news of drugs and danger in Colombia were rife and alarming. I was delighted to be heading for Peru, on my first ever foray to South America as a wildlife expedition leader, and skipping Colombia by air. That was the plan, but it did not unfold as I had expected.

Missed flights, missed connections, and flight cancellations meant not merely that I was to experience a forced stop in Bogota, but also a forced overnight. The airline appointed hotel was a long taxi ride away from the airport, and came without the warning that unless it was shared the return taxi fare exceeded the cash float each of us passengers had been given. Fortunately, having coincidentally buddied up with another Lima-bound passenger, the unexpected journey and overnight passed without incident, though the return to the airport the following morning was to a scene of total apparently caffeine-fuelled chaos as hundreds of people clamoured for seats on seemingly non-existent flights. With a little lateral thinking applied, my new buddy and I circumvented the crowds at “our” airline, booked new onward flights, charging them back to “our” airline, and when later we finally landed in Lima we parted firm in the expectation and belief that neither of us would ever visit Colombia again. That expectation didn’t unfold as I anticipated either.

The following two decades passed only with regular media confirmation that Colombia was notthe place to visit if one valued personal safety, the catchwords were: drugs, drug cartels, and murders. In short, Colombia was far too dangerous to consider as a tourist destination. Yet much has changed in the last twenty years, so much so that I was finally tempted back there last year, and yes I have already returned there this year! I was tempted there of course by the fact that Colombia hosts some 20% of all known birds species, and with nearly 1,900 species recorded there so far (that is well over a 1,000 more than have been recorded in Japan) Colombia tops the world ranking in terms of avian biodiversity. However, the adjectives I use now to describe Colombia are colourful, diverse, delightful, friendly, welcoming, and indeed packed with bird species. Far from warning-off others from going there my advice now is “Go! Colombia is a great Destination”.

Colombia’s avian diversity stems from its extraordinary diversity of landforms, environments and habitats. It has both Caribbean and Pacific coasts, it has high mountains and forested lowlands, not to mention ancient and modern cultures. In the centre and west of the country the northern part of the great Andean mountain range splinters into three separate ranges each slope of which differs climatically, floristically and faunistically from the rest. In the far north of the country, and very close to the Caribbean coast, lies the granitic massif of the Santa Marta mountain range. With peaks rising to over 5,700 m this is the highest coastal range in the world and it has been long isolated from the Andes far to the south and the central American land bridge to the north. In that long isolation, innumerable local endemic species of plants, insects, amphibians and birds have evolved here in situ, making it a fabulous area for a naturalist.

In the east, the great plain spanning from the Andes to the Orinoco, and bordering Venezuela, stretches out in the largest savanna in South America, known as the Llanos. In the south, in a tail-shaped extension of the country between Brazil to the east and Peru to the west, Colombia’s lowlands extend into the hot, humid Amazonian rainforest, in fact the lugubrious flow of the great Amazon River marks Colombia’s southern boundary. From that river’s bank in the border town of Leticia I could look eastwards from Colombia into Brazil, meanwhile a rainstorm was brewing to my right – just over the river and in Peru to the south – giving me three countries in one view.

From frost and snow in the high alpine Paramo habitat of the Colombian Andes down to the endlessly moist hot tropical rainforest, and from the rugged Pacific coastline in the west to the swampy grasslands of the Llanos in the east, the physical landforms and habitats of Colombia are not merely diverse, they are extraordinarily diverse.

While the grasslands of the Llanos are, undoubtedly home to some spectacular wildlife, from capybara and caiman to Orinoco Goose and Scarlet Ibis, they are outshone by the combination of extraordinary wildlife, accessibility, and lovely accommodations of the Brazilian Pantanal (ecotourism facilities in Colombia are still playing catch up with neighbouring Brazil, Ecuador and Peru). The unbroken rainforest with the meandering tributaries of the mighty Amazon in southern Columbia is indubitably overwhelming with its bewildering barrage of night sounds, its plethora of birds and its scarce and elusive mammals, but my sense is that Brazil, Peru and Ecuador can trump Colombia there.

For me, the most powerful memories I carry of the uniquely Colombian land forms and of the avian diversity of Colombia are of those fragmented northern Andean regions, of the Santa Marta Mountains, and of the Paramo, and especially of the country’s hummingbirds. Seeing thirty or forty hummingbird species in a matter of days, which to me seems staggering, is, in Colombia, quite normal. In each habitat, at each elevation, one can expect to encounter different species.

Biologically and taxonomically the hummingbirds differ in intriguing ways one from another, yet at a very much simpler level, as living jewels, as creatures of extraordinary beauty, and phenomenal activity, they are overwhelmingly thrilling to watch. Their feathers appear as if beaten from precious metals, and their names stretch the imagination hinting at the desire of the ornithologists naming them to find ever more fanciful appellations. Those designations range from ‘hermit’, ‘sylph’ and ‘trainbearer’ to ‘thornbill’, ‘metaltail’, ‘saphirewing’, ‘plumeleteer’, ‘violetear’, ‘jacobin’, ‘sabrewing’ and even ‘woodstar’. No fantasy author naming fairies could do better.

To the specialist ornithologist, hummingbirds differ structurally in the lengths of their bills, in the patterning and iridescence of their plumage, in the flowers with which they have intimate associations (they have co-evolved and have bills that exactly match certain types of flowers allowing them to reach deep into the nectaries and so be used by the plants as agents of pollination), in the habitat in which they occur, and the altitude at which they can be found.

To the casual observer and bird watcher, it is the vibrant colours and the extraordinary speed and aerobatics of hummingbirds that makes them such a delight to watch. Ranging in size from 5-22 cm in length and 1.6–21 g in weight and occurring from sea-level up to 5,000 m, the 330 or so species of hummingbirds are all confined to the New World, from Alaska to Chile, but mostly in the Neotropical Region of Central America and northern South America. This extensive order of birds, the Trochilidae includes the world’s smallest avian species – the Bee Hummingbird of Cuba. Superlatives aside, this is an extraordinary order of birds.

From stationary hovering flight in front of a flowering shrub, the average hummingbird (thanks to extraordinary modifications of its skeleton, wing musculature and heart) is capable of slow motion forwards and even backwards flight. Beating its wings at blurring speeds, its wing tips describing figures of eight in the air, a hummingbird can dip its bill in and out of a flower’s corolla in order to sip at the rich nectar within – the hummingbird’s aviation fuel.

While feeding, the hummingbird’s motion is paradoxical. At one and the same time its body, and its position in relation to the flowers at which it feeds, changes only slowly, yet to remain so poised and almost motionless in the air it may be breathing at up to 500 breaths each minute and beating its wings as many as 80 times each second – no wonder hummingbird wings blur to our eyes and whir to our ears.

Between their slow motion visits to flowers hummingbirds turn on breath-taking bursts of speed. They are so swift from a seeming standing start that it is as if they enter warp-drive. They appear to burst out of one reality, dematerializing into the ‘hummingbird zone’; then they rematerialize hovering again before another flower many metres away. I never tire of glimpsing these seemingly random bursts of immense speed, their blasts of colour, and their phenomenal aerobatics. I simply cannot imagine what it must be like to have their eyes and brain capable of processing so much visual information at once during their high-speed flight.

Colombia offers not only a plethora of hummingbird species to admire, but also a number of lodges, restaurants and hotels that provide well-stocked hummingbird feeders in order to attract their local hummingbird species and to mesmerise their human guests. And now, having finally gained a liking for coffee, I can enjoy a taste of Colombia, while admiring some of my very favourite birds.

Roll on September 2019; I can’t wait to return to Colombia.

Outro

In June 2018, Mark’s latest book, A Field Guide to the Birds of Japan, will be published.

If you would like to read more about Japan’s natural (and un-natural) history, then you may enjoy Mark’s collection of essays entitled The Nature of Japan: From Dancing Cranes to Flying Fish.

Author, naturalist, lecturer and expedition leader, Dr Mark Brazil has written his Wild Watchcolumn continuously since April 1982, first in The Japan Timesfor 33 years, and since 2015 here on this website. All Wild Watch articles dating back to 1999 are archived here for your reading pleasure.

Two handy pocket guides The Common and Iconic Birds of Japanand The Common and Iconic Mammals of Japanhave also been published and along with The Nature of Japanare available from www.japannatureguides.com